Thursday, Knox lawyers will argue to First ("Murders") Chamber of Supreme Court that Florence court's Calunnia II conviction of Knox was wrong. Uphill battle. Florence reasoning has been widely praised.

Tuesday, January 21, 2025

Mind Game: My Lawyer Persona Represents Knox On Night Of Arrest

Posted by James Raper

Central Police Station; girls’ house over hill at rear

Mind Game

I have sometimes thought – none too clearly it has to be said - what might have happened had Knox had a legal representative with her when she was interviewed by the police about the exchange of text messages on her phone.

The easiest way to do this, since I have often attended clients at the police station, is to envisage what might have happened had I been that legal rep. This, therefore, is a thought experiment based upon my own knowledge of the case, that is the material that arose during the trial, the law, police tactics/ethics/professional standards etc as would have applied had the interview occurred within my own jurisdiction.

I may get a bit Mickey Spillane with the following.

I see myself arriving at the Questura and seeking initial disclosure before speaking to my client in private. I expect that the police would tell me about the murder and that my client was a flatmate of the murdered girl.

The murdered girl was a Meredith Kercher and that she had been found in her bedroom at the cottage which my client shared with her and two other girls, with her throat slashed. The best estimate they had as to time of death was that the murder had occurred overnight on the 1st/2nd November.

My client, Amanda Knox, had told them in various verbal and written statements that she had been with her boyfriend at his flat at that time.

That had been what the boyfriend, Raffaele Sollecito, had also said, but now he had contradicted that saying that my client left him earlier that evening and had not returned until about 1 am. The boyfriend had told the police that he had been persuaded by my client to give the police a false version of events but had not elaborated further on that.

In view of this contradiction to what had hitherto been a joint alibi they wanted to interview my client for her explanation of this development and to find out if she had any further information to give which she had not so far given, and if so, why not. The suspicion they had was that she had, at best, deliberately misled the police as to her alibi, for whatever reason, and at worst, that she had done so to avoid her own involvement in the murder being investigated.

So yes, having come to the Questura voluntarily initially she was now being detained for the time being, that is, under arrest, as was Sollecito.

Other than the foregoing they had no actual evidence of my client’s involvement (at least that they were prepared to disclose). I am going to assume also that my client had been told about the position concerning Sollecito, that she had told me this when she phoned me to request my assistance. After all, why would she need a legal rep unless something had just gone pear shaped.

I therefore go to see my client. She wants to talk a lot straight away but I shut her up immediately and give her the well rehearsed introduction as to who and what I am, what I am here to do for her and what I have been told by the police.

I tell her that murder, short of treason, is the most serious criminal offence there is, and if the State were able to prove her involvement in the death of her flatmate, then she could expect a mandatory life sentence.

Waiving away any possible protestation of innocence I tell her the good news is that the police apparently have very little to go on in that respect, in fact nothing but an alibi that does not now stand up, and that’s what they want to question her about.

I tell her that what we discuss, what she tells me, is confidential and privileged. I will not say anything to the police without her consent.

There are, however, some professional rules by which I must abide. If she discloses some fact which is self incriminatory (at worst, for instance, that she did murder Kercher) then although I will not tell the police, I will not sit silently by her side in the police interview as she denies it. I will not be complicit in that and will excuse myself from the interview and, furthermore, not act for her any more.

She needs to understand what is kosher but, of course I am here to advise her every step of the way, so long as I am still acting. I tell her that although she will be questioned she does not have to say anything other than to confirm her name, date of birth, address, and nationality. Anything she does say will be recorded and may be used in evidence against her.

However should she have an explanation in response to a question then a refusal to offer that up at this stage might go against her should she then want to rely on such an explanation at a later date. Any questions that stray off track and have anything to do with her possible involvement in the murder are a definite no-no and she should simply reply “No comment”.

I will be there to ensure that there is no “fishing “ by the police and that she goes “No comment” when appropriate. It is, after all, up to the police to prove a case and she does not have to give them any help.

As to whether she has committed another offence for which she can be charged, such as lying to the police as to her whereabouts for the purpose of an alibi, then that is unlikely unless it can somehow be stretched to perverting the course of justice which again, I advise her, is very unlikely.

I then ask her whether she has an explanation for Sollecito’s behaviour. If what Sollecito had said were true, then can she give an innocent account of her whereabouts up until about 1 am, preferably with witnesses to back it up?

If she can then she can expect the police to try and verify or disprove that account. Furthermore, if she could do so, why had she not already done so? Perhaps she was just waiting for me. If Sollecito was lying, had she any idea why?

Now I am guessing here, obviously, but it seems fairly clear from the stance she took at trial that she is not about to concede that she had been away from Sollecito during the relevant time period. Nor tell me that if she was, she had an innocent explanation that she could give, which anyone could at least try and check.

So she doesn’t say anything on that score but on the question of why Sollecito would lie, she has two options: she could say “I don’t know, what he says isn’t true” or she could try a bit of mind reading.

However I think it likely that she would have done the first and only then set about the second.

She tells me that she stayed with Sollecito. Normally she would have gone to work but that night she had a text message from her boss telling her that she didn’t have to turn up.

She doesn’t understand why Sollecito would lie to the police. All she can think is that he, like her, had walked into a situation he had never been in before, got scared, and must have been trying to find a way out by disassociating himself from her (the explanation she gave in her Memorial).

I let it rest as to why he would have been scared but I assure her she has no reason to be scared. I ask her if she has her phone but of course this had been taken off her when she was detained. I ask her to tell me whether there might be anything recorded on the phone that might be incriminatory. She could be asked about that during the interview. She says no.

Now there are some legal reps who simply insist that their client say nothing to the police : “say “No Comment” all the way through”.

I am not one of them as there are circumstances where I judge that it is probably in their best interest to co-operate, unless, that is, I have some very bad vibes from the police disclosure, or from my client. In this case I have got neither.

Furthermore my client wants to be released as soon as possible and a “No Comment“ interview would potentially hinder that outcome, which I have already in mind to argue for quite forcefully when the interview is over, whatever their suspicions. She should respond to their questions in the same way she has with me. My client is happy to proceed.

And so into the interview which I expect will not take long.

It is to be tape recorded. There are 4 other people there. We are all seated round a table. Inspector Rita Ficarra is to lead with the questions, assisted by Officer Lorena Zugarini. They are on one side, I and my client sit on the other side.

To one side, but next to my client, sits the interpreter, Anna Donnino. Just as well as I cannot speak a word of Italian! (I have dropped Ivano Raffo from this scenario as otherwise it would be getting a bit crowded.)

The tape is switched on, introductions are made and my client is read her rights and given the prescribed Caution.

Ficarra recounts what Sollecito had said during his interview with them, pointing out that what he had said contradicted what Knox had been telling them about her whereabouts. Had she in fact left Sollecito’s apartment in the evening of the 1st November, returning at about 1 am? My client replies “No. I don’t understand why he would have said that.” Had he left and she stayed? Knox replies “No. We were together all the time.”

Ficarra looks sceptical and produces Knox’s phone. “You sent a text to someone at 8.35 pm, just a few hours before the murder, in which you indicate that you’re going to meet up with him, or her, a little later. Who was that?”

WOAHH! I suspect the police of having had this information and of not having disclosed it to me when I arrived. I look at my client. My look says “Anything to worry about?” She shrugs her shoulders but looks irritated and confused at the same time.

Ficarra continues before any response can be formulated. “You were responding to an unidentified text that has been deleted from your phone. What did that say and who were you communicating with?”

At this point I want to stop the interview and have a private word with my client. My client has already told me about the text she received but not about the reply and a meeting. I ask for a break so that I can consult with my client.

Ficarra will have none of it. She says “Miss Knox has already had the benefit of legal advice from her rep. She is now in a recorded interview and being asked questions – quite simple questions – which she can choose to answer or not. The interview will continue. She says she did not leave Sollecito’s flat and if true she should have nothing to worry about. We need her co-operation and (looking at my client) she has been very co-operative to date.”

I interject and ask to see the text message. Ficarra places the phone in front of me and my client. I read “Va bene. Ci vediamo piu tardi. Buona serata.”

Now my Italian is rubbish but with the benefit of a bit of Latin and French even I can see that this does not add up to much. Loosely translated I read “OK, See you later. Good evening.” I say that out loud and look across at the interpreter. She nods her head.

But then there is the deleted text (on my client’s phone) and who this other person is.

Again I look at my client. She responds spontaneously to my look. “See you later? That doesn’t mean that I was going to meet someone. That’s just something one says”. I nod.

Ficarra continues. “We are conducting a murder investigation and we need to trace and interview the person you were texting. Who is it?”

My client looks puzzled if not a bit stunned. Not what I was expecting. What’s the problem?

Knox says “I don’t remember.”

Ficarra presses her. “Think.”

The interpreter jumps in at this point, telling my client that memory can be effected by trauma and giving an example from her own experience.

Again I say “I do need to have a word with my client. You have brought up something that was not disclosed to me and if you persist on your right to continue and to ask my client questions, then I will direct my client, each time, to answer “No Comment”.” I give my client a long look to make sure that she has got the message too. It appears she has.

Ficarra nods in exasperation and the tape is switched off.

When we are alone together I ask my client why she can’t remember and if there is a problem. I ask her to bear in mind my previous advice. She tells me it is her boss Patrick Lumumba and that she works a couple of evenings each week at his bar, “Le Chic”.

I ask her if there is any reason why she would not want to tell the police this. She shakes her head. I tell her that if that’s the case then it would be in her best interest to tell the police that she does remember now and that it was Patrick Lumumba.

However I also tell her that the police will certainly check with Lumumba and ask him for his version of what the text exchange was about.

Knox nods but still looks concerned. I notice that and again ask if there is anything else she wants to tell me. She says no. Only after Lumumba’s arrest do I (or the police) learn that in his deleted text to her he had said that she would not be required for work that evening.

The interview re-commences. I tell the police that my client has a short statement which she wishes to make. This statement basically just confirms what she had told me about Lumumba and her employment at Le Chic. Ficarra thanks my client for that but wants to probe a lot deeper.

Doesn’t “See you later” suggest a meeting later that evening and why did my client not mention any of this in the statements which she had already given to the police?

Knox says that no meeting had been or was being suggested and that she hadn’t mentioned it previously because it didn’t seem to be relevant – not, incidently, because she had been unable to recall the exchange of texts. That was my first warning that she could be unpredictable, indeed untruthful.

Also flashing up in my mind was the disclosure I had received that Sollecito had said that he had been persuaded by Knox to give a false version of events.

I had indeed mentioned this to Knox at our initial meeting. Was the issue of relevance an easier thing for her to put forward than a lack of memory on her part, which, whenever mentioned, only ever seemed to provoke further discussion?

Was that what she was trying to avoid? Ficarra certainly seemed to think so because she immediately mentions this to my client. Why had my client put him under pressure to give a “false version of events”?

I interject and say that my client, quite clearly, disputes what Sollecito had told them. Knox adds “He is not telling the truth”. I’m going to wrap things up for my client now and tell the police that on my advice she will now answer all further questions with “No comment”.

Ficarra, however, presses on but is met with “No comment” each time. That said some of those further questions are certainly food for thought, and are going to make my overture to the police to release my client, whether unconditionally or on bail, somewhat more complicated.

Why, in Filomena’s room, was there glass on top of the scattered clothing rather than underneath, which would be the case if the break-in was genuine? She mentions a host of other observations, all indicative of a staging. Who would be most likely to have an interest in a staging, she asks my client? Again “No comment”

Why is my client’s lamp on the floor in Meredith’s room, behind a locked door?

“No comment”.

Why are there no visible prints in blood between the blood in Meredith’s room and the footprint in blood on the bathmat in the small bathroom? Somebody must have removed them. Was it her?

“No comment”.

And so on, basically a trawl through all the circumstantial evidence the police had accumulated by this point in time. Much of this stuff, admittedly, was not mentioned in disclosure, but the police are still entitled to bring it all up.

And perhaps this is what Knox meant when saying, later, that she had been told by the police that they had (in her own words) “hard” evidence against her. And perhaps this is what Knox had in mind when saying, later, that the police had told her they had (in her words) “hard” evidence against her?

Ficarra’s tactics here are obvious. She is trying to unsettle my client, and she is succeeding, not that I can do anything about it. Knox looks pained and unsettled. She is holding her head in her hands. I point that out to Ficarra, telling her that my client is obviously distressed and needs a break from the questioning.

Ficarra nods and the tape is switched off. However she tells me, and deliberately in Knox’s presence, that there will be further questions for my client, that the police are waiting on forensic results, and a search of Sollecito’s bedsit, and that although a matter for the custody sergeant, and ultimately for the Superintendent at the station if an extension of detention is required, she will be opposing police bail, until this is all out of the way. Clearly she thinks that my client is somehow involved in Meredith’s death.

Suddenly there is an outburst from my client. “It’s him. It’s him!” This is not recorded on tape because it has been switched off. I now ask for time to consult with my client. I can see that the request pains Ficarra but after a moment’s hesitation she nods in agreement.

Back in private conference with my client, she tells me that, although her memory is confused, she is now able to remember, in flashes of blurred images, that she had been in the cottage and that Lumumba, who had accompanied her to the cottage, had attacked Meredith and had murdered her. The trauma of the event had blocked the memory until now. Well, at least that explains the memory problem.

I point out what my client has in any event fully appreciated, that the “It’s him. It’s him!” bit (be it not on tape) certainly needs to be explained to the police. It will only increase their suspicions about her if it is not.

The interview will have to be re-started. My client can give the police the above information, just as it has been given to me. Indeed the information should lessen their suspicion of her involvement in the murder since it is adequate and believable.

Furthermore she is now an extremely valuable witness in the investigation and that should also make it much easier for me to seek her release on bail, though that cannot be assured, and she might have to await Lumumba’s arrest. She has committed no crime that I am aware of.

She may have let the perpetrator into the cottage but an innocent explanation for that would surely be available. As my client is desperate to be out of detention she agrees to the foregoing.

But what actually happened was that her further detention was authorised and Knox, in a pique, dispensed with my further services.

What I could not have known, of course, was that Knox had been lying about Lumumba. Perhaps I should have factored in that possibility? Should I have explained to her that if she was then that, in itself, would expose her to a criminal charge (in Italy at any rate, though here in England we do not have, specifically, a similar criminal offence) or would that not have made a difference?

I go home to bed. I have a long day ahead tomorrow.

Monday, November 11, 2024

Amanda Knox Said To Be Almost Certain To Face Murder Retrial Now

Posted by Peter Quennell

Tweet near end of 1st appeal; bent not-guilty verdict was annulled

1. Knox’s Self-Imposed Trap In Headlines

Millions of Italian-Americans including politicians in both parties have been disadvantaged by the dozen years of mafia-tool Amanda Knox’s endless bigotry for cash. Now this circles back to bite her.

Above: Associated Press report 17 April 2017 on 2000 websites

Above (html): May 2017 op-ed by Knox in the Los Angeles Times

Above (pdf): May 2017 op-ed by Knox in the Los Angeles Times

Above: 4 May 2017 report in SeattlePI carried by numerous media

On 20 January 2025 Mr Trump will be back in power. There is already movement behind the scenes to have Knox sent back to Italy for a retrial, this time without mafia or Knox-PR meddling.

2. The Wider Context

Back in 2008-2009 the rabid Knox PR headed by David Marriott (now deceased) made a beeline for any American with influence to whom they could lie about “no evidence” and “persecution of a fellow citizen”.

Then-private-citizen Donald Trump (and fellow New Yorker; I encountered him a couple of times, not to talk to) was lured into this trap, and he spoke up sharply against Italian justice at the end of the 2009 Massei trial - to no effect of course.

This post of 18 December 2009 resulted.

Mr Trump did not really dig further, or follow up much - his main beef in 2009 was said to be that his first wife was living in Italy with a rich Italian. (She later moved back to NYC and relations were good when she passed on.)

This post of 18 August 2011 resulted.

Later in 2011 in the final days of the Hellman appeal Trump tweeted that Italy should be boycotted if Knox failed her appeal. He was obviously not made aware that he was a strange bedfellow with the Italian mafia.

Knox was (illegally) sprung by Judge Hellman with, well, mafia influence, with some pressure on the President of the Republic (head of the Italian justice system) from the Obama administration (also extensively lied-to by the rabid Knox PR).

Trump and Knox then went their separate ways, until the post-2016-election fracas summarised in the headlines at the top blew up. You really should read how Knox bristled at Trump with her trademark ultra-pompous victimhood.

We have repeatedly emphasized (rebutting still-endless false claims by Knox and her almost defunct bandwagon) that Knox was never “exonerated”.

This post of 23 June 2017 mainly drafted by the formidable Italian legal expert Machiavelli explains the legal situation.

The final (corrupted) Supreme Court appeal which Knox provisionally won can readily be reversed, by the President of the Supreme Court or the President of the Republic.

We hear that retaliatory action against Knox is already in the works. What so threatens Knox is not only Mr Trump.

It is also thousands of Italian-American politicians ON ALL PARTS OF THE POLITICAL SPECTRUM (this case has never been political), some of whom we are asked to bring up to speed on the hard facts of the case, who have had to sit and watched Knox fan anti-Italy and anti-Italian bigotry for blood money - for a dozen years now.

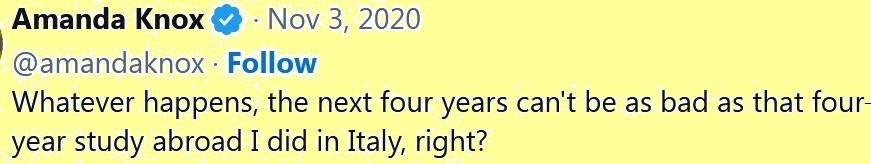

This is the November 3 2020 tweet sent out by Knox prior to the presidential election vote.

The next four years? For Knox? Not as bad? Actually… they can.

Thursday, September 19, 2024

Florence Court Explains Second Knox Guilty Verdict For Criminal Slander #2

Posted by James Raper

Sequential images all from courthouse; court was closed to press

Reflections

These are my reflections, as a lawyer, on the Motivation of the Florence Appeal Court re Amanda Knox’s conviction for criminal defamation of Patrick Lumumba

This appeal was heard in Florence before the presiding appeal judge Dr Anna Sacco and the reporting judge Angelo Grieco. The offence for which Knox was convicted was pursuant to Article 368 of the Italian Penal Code. It is worth stating the offence as follows –

Anyone who with a denunciation, complaint demand or request, even anonymously or under a false name, directs a judicial authority or other authority with an obligation to report, to blame someone for a crime who he knows is innocent, that is he fabricates evidence against someone, shall be punished with imprisonment from two to six years.

Knox had been convicted of the offence at trial in 2009 - where the evidence was that she had named Lumumba as Meredith’s murderer, effectively as a witness herself present in the cottage at the time - and then again on her first appeal before the Hellmann court in 2011, and then again on her final appeal to the 1st Chambers of the Supreme Court in 2013. Her conviction for the offence thus became definitive under Italian law.

Why then did the Italian Supreme Court (in Italy it was reported that it was the 5th Chambers) refer the conviction to the Florence Appeal Court for a review? I have my suspicions as to the 5th Chambers’ motive for taking this step but a more charitable and legalistic view would be that it was a tidying up exercise pursuant to an alteration that had been made to Italian law by a Legislative Decree in October 2022.

The Florence Appeal Court refers to this in its Motivation. Basically, the Decree states that henceforth there must exist a framework in the Italian judicial system for implementing, in it’s domestic law, decisions at the European Court of Human Rights that go in favour of the applicant. As to what is meant by “implementing”, in the case in hand, it must be that such decisions by the ECHR have to be, and have to be shown to be, taken into account in achieving the final verdict. In the event the 5th Chambers excluded any discussion, let alone a critique, of these decisions, by declaring that they could not be challenged.

That ruling, however, does not apply to us.

I had not, until now, known anything about the terms of reference laid down by the 5th Chambers for the Florence Appeal Court, other than what could be gleaned from social (and the largely unreliable) media. Having now read the Motivation I now know, as the Appeal Court refers to them.

The ECHR had found three violations, or rather procedural infringements, in the case, and it was on this basis that the 5th Chambers had made the referral.

The first was to do with Knox’s treatment at the Questura on the night of the 5th/6th November. Although the ECHR dismissed the claim (under article 3 ) that she had been subjected to inhumane or degrading treatment, it did say that there should have been “an effective investigation” by law enforcement and the judicial system “to identify and punish possible perpetrators”. What was meant by this I am not entirely clear. It surely cannot mean the perpetrators of the murder. We are dealing with the defamation here so it must be a reference to the behaviour of the police oficers and whether this had a prejudicial impact on the offence that then occurred. But what would constitute an “effective investigation” other than a trial of the accused on the charge, with the hearing and cross-examination of witnesses etc, which is exactly what came to pass? What, exactly, would have been the point of an earlier, and presumably less rigorous, investigation conducted, presumably by the said perpetrators i.e the police, or at any rate by those institutionally biased in favour of them? This makes little to no sense at all to me.

The second infringement (or violation, whatever you prefer) was to do with Knox’s lack of legal representation. The ECHR had determined that Italy “had failed to demonstrate that the restriction of access to a lawyer had not irrepairably affected the fairness of the process as a whole”. This is taken by Knox supporters as a statement that the outcome (the verdict) had been irrepairably unfair, and accordingly the verdict should be squashed.

The statement, in one brief sentence, puts together, sequentially, as if one entailed the other, the bones of a premise and then a conclusion, even if the conclusion was not expressly stated. To my mind, there is no logical structure here such as would enable anyone to draw a valid conclusion from it. There is clearly something missing. The missing part (well it is there but cleverly hidden) is an assumption, or an additional premise that holds that “restriction of access to a lawyer is irrepairably unfair”. On the face of it that might also appear a reasonable proposition. So, insert that and then at least we have a logical argument, as follows –

Restriction of access to a lawyer is irrepairably unfair

Italy failed to demonstrate otherwise

Therefore the “process” was irrepairably unfair

But the conclusion to even a seemingly valid logical argument can be unsound and the above, as it relates to the case in hand, is unsound.

For a logical argument to be sound the premises upon which it is built have to be established as true in the given circumstances. There is a reason for why the aforesaid premise is missing. It is both untrue, in the given circumstances, and highly loaded (the use of the word irrepairably!)

The assertion, as it stands, without the missing premise, is pure sophistry, and begging the question, the petitio principii fallacy. The concept of it being irrepairably unfair is as much a part of the premise as it is the conclusion , which the conclusion then expands to “the process as a whole”. Whether Italy did, or did not, fail to demonstrate otherwise is actually irrelevant as to whether what happened was fair or unfair.”

In fact it was the ECHR which had failed to demonstrate required truths. It had failed to demonstrate

(a) that Knox did have her access to a lawyer restricted. The only person who claims that this was so is, of course, Knox herself. Was the State under an obligation, in the circumstances, to ensure that she had a lawyer whether or not she wanted one? It seems to be only in retrospect that she says she did want one.

(b) that her untrue accusation against Lumumba was in fact connected to and part of, that is that it arose from an unfair “process as a whole”, whatever that means, but let us restrict it to the absence of a lawyer in this instance. Without this the logical argument is meaningless in so far as it relates to the matter in hand.

(d) that, and of course this is the crux of the matter, restriction of access to a lawyer was, in the circumstances, unfair and, indeed, irrepairably unfair.

Whether it, and the other two procedural infringements, were unfair, let alone in the case of the absence of a lawyer, irrepairably unfair, and had a material and substantive adverse impact upon the safety of the conviction for slander, the ECHR did not attempt to establish as it would under the terms of Italy’s treaty obligations as to the Convention have to be a matter for an Italian trial court to investigate and rule upon, in accordance with the law and on the evidence before it.

The ECHR would know that, and that it was a matter more appropriate for an Italian court but now with regard to the concerns the ECHR had expressed. Indeed I see the above statement as being little more than saying that. Had it been more than that, and had it been within it’s remit, then the ECHR could have, but did not, declare, in unmistakable language, that the lack of legal representation, and the other two infringements, in the precise circumstances at the time, was unfair, and impacted on what happened next – with a precise explanation as to why it so held. That it did not speaks to an understanding on it’s part that it was not competent to the task and that the task was beyond it’s remit and the generalities of Human Rights Law.

As far as Italian law itself is concerned we have (in so far as relevant) Article 63 of the Italian Procedure Code. This states that if a person who is not accused or a suspect makes self incriminatory statements to the criminal police, then the proceedings must be terminated and the accused/suspect warned that investigations may be carried out on him and that he should appoint a lawyer. If the person should have been heard as an accused or suspect from the beginning his statements shall not be used. Nothing unfair in any of that.

It is, of course, arguable that Knox had made herself a suspect when she declined to co-operate with the police over the exchange of texts with Lumumba, but even so surely only as a suspect in the murder case or, at the least, suspected of withholding information in relation to that investigation, not that she had made any self-incriminatory statements up to then, or prior to the slander of Lumumba. Actually, I would go further and say that she should already have been a suspect due to Sollecito’s prior dismissal of her alibi. However, at no stage could she have been a suspect for the offence which she then committed. One cannot be a suspect for an offence that has not yet occurred. However at the point when that did occur, Article 63 would apply. Although it is difficult for me to see how that would have assisted Knox, perhaps it played into the 5th Chambers terms of referral which excluded the Appeal Court from giving any consideration to the 1.45 and 5.45 statements that Knox signed, contrary to the ruling by Gemelli at the Supreme Court in 2008 which held them to be admissable in respect of the charge of slander only.

To be fair to the ECHR neither the trial court nor any subsequent court actually addressed the obligations imposed upon Italy by the Convention on Human Rights in their respective Motivations confirming the convictions for slander, and had they done so then perhaps that would have gone some way to mollifying the ECHR. But that is not to say that, as judges, they had not done so. A beneficial by-product of the Legislative Decree may well be that in future judges will deal have to do so to avoid being thus ensnared.

The third infringement was that the Interpreter had been too familiar with Knox and had led her on to believe that she had amnesia. This, to some extant, actually accords with the testimony of Anna Donnino.

In short, according to the 5th Chambers, these infringements may have been procedural but they had a “decisive impact (here the 5th Chambers, in the rather dogmatic and pre-emptive fashion with which we have become familiar, enters on the merit following on from a definitive verdict with which it had previously agreed) on the very moment of (Knox) making the slanderous accusations in the 1.45 and 5.45 statements.” The ECHR had not said as much. The statements therefore had to be removed, the 5th Chambers ruled, declaring that only it had an interface with the ECHR and thus be able to interpret it’s rulings! The Appeal Court, in it’s Motivation, refers to this as a “peremptory” ruling, hardly bothering to hide it’s disgust with it.

However the Appeal Court also pretty much has it’s hands tied by the effect of Article 628 which states –

“In any event a verdict (in this case the annulment of the conviction for slander) issued by a court following a Cassation [Supreme Court] order of remand may be appealed only on reasons that do not concern those that had already been decided by Cassation on the order of remand….” As it was the 5th Chambers which issued the verdict and order of remand this has the hallmark of a self entitled student being allowed to mark his own work! Nevertheless the Court of Appeal had to be careful and not fall into the trap laid for it.

What we are left with, thanks to the 5th Chamber’s (nudge, nudge, wink, wink) interface with the ECHR is the Memorial. The Memorial (the 5th Chambers said) remained to be assessed as it could not be said that it was impacted by the aforesaid infringements.

The 5th Chambers went on to say that there were 2 unanswered questions in this respect. I have to paraphrase what these were as the Motivation is a bit obtuse at this point, but they come straight out of the same playbook used by the 5th Chambers in acquitting Knox and Sollecito in 2015.

1. Does the content of the Memorial imply the existence and content of the slanderous statements at 1.45 and 5.45? This looks to me pretty much like a trap for the Appeal Court.

2. Is the Memorial to be taken as a retraction or confirmation of the slander?

Entry in to the merit was provided for by the Legislative Decree but that was not for the Supreme Court at this stage. Hence the referral. However we have to worry that the matter might come back to the 5th Chambers on appeal.

In the final analysis the terms of referral for the Appeal Court was that it “had to determine whether, in the light of the false evidence, the Memorial written by Knox contained statements accusatory against Lumumba made in the knowledge of his innocence, such as to uphold the guilty verdict at 1st instance”.

The Appeal Court took into account the submissions of interested parties.

According to Knox’s defence the Memorial was nothing more than a dreamlike account of fragments of a nightmare that Knox doubted had any connection to reality; flashes of blurred images etc. Furthermore, the police had already formed an investigative hypothesis of Lumumba’s involvement in the murder given that his detention was authorised (at the same time as Knox’s) at 8.30 am on the 6th, which was well before Knox (at around 13.00 hours) asked for paper on which to write her Memorial. Thus it was not the Memorial that instigated his arrest! No, it was plainly Knox’s earlier accusations. It is all really rather Fawlty Towers, isn’t it? Think Basil Fawlty and “Don’t mention the war!” when some germans come to stay at his Guest House. Here it is don’t mention the statements at 1.45 and 5.45! Also the language of the Memorial fell short of the necessary intent to commit the crime. I will come to how the Court of Appeal dealt with these submissions shortly.

Of course, in addition to the Memorial there is Knox’s letter of the 7th November which is likewise unimpacted by the aforesaid infringements.

The Appeal Court went through both documents with a fine tooth comb.

The Appeal Court also listed the submissions on the part of Lumumba. In my opinion it was rather clever in doing this as the effect was to destroy much of the subversive agenda that lay hidden in the 5th Chamber’s terms of referral all the while avoiding any charge that the Court of Appeal was itself challenging those terms. Indeed the Court of Appeal disposed of a number of these submissions in a manner making it clear that it had fully got the message from the 5th Chambers.

One of the Lumumba defence submissions was that, taking into account the first infringement mentioned by the ECHR, there needed to be a Review of Procedure hearing. That was not accepted by the Court of Appeal as it was not in the terms of referral it had received. In any event we can mention here, be it not menioned by the Court of Appeal itself, the following remark by the 5th Chambers in 2015 –

“And also, a possible decision of the European Court in favour of Ms Knox, in the sense of a desired recognition of non-orthodox treatment of her by investigators, could not in any way affect the final verdict, not even in the event of a possible review of the verdict, considering the slanderous accusations that the accused produced against Lumumba consequent to the asserted coercions, and confirmed by her before the Public Minister during the subsequent session, in a context which, institutionally, is immune from anomalous psychological pressures; and also confirmed in her Memorial, at a moment when the same accuser was alone with herself and her conscience in conditions of objective peacefulness, sheltered from environmental influence; and were even restated, after some time, during the validation of the arrest of Lumumba, before the investigating judge in charge.”

Another was that in the Memorial, which was, indeed the crux of the referral, Knox had specifically mentioned her earlier statements – “and I stand by my statements that I made last night” - and thus it was clear from this that she had full recall of their content, and stood by it. The Court of Appeal did not fall into the trap, but re-iterating this submission in the Motivation speaks for itself.

Another, in aid of the foregoing, was Knox’s letter of the 7th November, in which Knox claimed that she had not lied and stated that “I really thought he was the murderer”. In addition, Amanda Marie Knox, at the hearing on 8 November 2007 validating the arrest before the Judge for preliminary investigations, had made use of the power not to reply and, therefore, neither at that meeting nor at any time thereafter had she or her lawyers represented to the investigators the innocence of Diya Lumumba, and yet that she was already perfectly aware of her guilt as to the slander is apparent from the content of her conversations with her mother, and then both parents together, in prison.

Turning to the Knox defence submission that a proper interpretation of the Memorial was that it contained a retraction of the accusatory statements, the Court of Appeal was of the firm view that this was not acceptable.

The Court of Appeal said – “the incidental reference in the grounds of the judgment of the ECHR to the content of the Memorial, in the sense of the alleged retraction of the statements previously made by Amanda Marie Knox, in that case evidently inferred from the interpretation given by the Court of Assizes of Appeal of Perugia in the judgment of 3 October 2011 (Hellmann, annulled by the ruling of the Court of Cassation), is therefore not relevant for the assessment of the substance to be carried out in this case. It follows that the defense, which seeks to give the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights of 24 January 2019 a broader scope than the actual one, which also extends to a binding interpretation of the substance of Knox’s Memorial of 6 November 2007, going beyond the provisions of the judgement of the Court of Cassation of 12 October 2023 (annulling the conviction and setting out the terms of referral), is therefore unfounded.”

On the Knox submission that the Memorial contained nothing but the fragments of a nightmare dimly remembered, the Court of Appeal considered whether there could be any reasonable doubt as to Knox’s ability to distinguish between reality and unreality and, indeed, whether this was relevant to the issue in hand. It was not just a case of having flashes of blurred images as Knox herself had referred to them as flashbacks –

“In the flashbacks I’m having I see Patrick as the killer, but the way the truth appears in my mind……. there’s no way for me to tell you, because I don’t remember for sure if I was at the house that night.”

The Court of Appeal, referring to Case Law, stated that doubt is only relevant to the material element of an accusation if that element does not have the character of seriousness, or is absurd, unlikely or grotesque. Even then, doubt is irrelevant if the accuser is aware of the innocence of the slandered person.

“The case law has long made it clear that the crime of slander is supplemented even if the criminal liability of a third party is maliciously put forward in doubt, provided that the complainant is aware of the innocence of those who are indicated as possible offenders.”

Logic comes into play here because if she was there, as she was definitively held to be by the 5th Chambers upon her acquital, then she must have been aware of Lumumba’s innocence and even if she was not then she must have been aware that she was fabricating evidence against him.

Furthermore the dream theme pushed by her defence is contradicted by the thread of the circumstances related by her flashbacks. Meeting Lumumba on the basketball court, then with him at the door to the house, then she curled up in the kitchen with her hands over her ears as Meredith screamed. That screaming was heard by witnesses but not suggested to her by Mignini or anybody else. Such a thread with evidential elements in support, is inconsistent with the disassociated fragments of a nightmare.

“The indication of Lumumba as the perpetrator of the murder is explicit and precise in the Memorial, written by the defendant autonomously and in solitude, in her own language and in her own hand”, the Court of Appeal held.

On the matter of intent, again this is irrelevant.

“According to the settled case-law of the Court of Cassation, slander is a crime of danger. The question to be assessed is whether, in the present case, Knox’s conduct was liable to create a risk of criminal proceedings being initiated, a requirement which can be regarded as inadequate only where the false accusation has a purpose which is manifestly and prima facie unlikely or incredible by reason of the circumstances in which it was carried out, the manner in which it was expressed or the absolute unreliability of its content, so that a finding that it is unfounded does not require any investigation. Only in such cases can the action be regarded as lacking the ability to harm the interests protected by the offending rule and constitute a criminal offense impossible under Article 49 cod. pen.

On the other hand, for the offence of slander to be capable of being characterized, it is only necessary that the false accusation contains in itself the necessary and sufficient information for the initiation of criminal proceedings against a person who is unequivocally and easily identifiable, as was certainly the case - even nominally and documentally - in the present case.”

By and large I think this is a well argued Motivation, it covers all the basic points and does nothing to put itself at odds with it’s terms of referral. It established, despite the bizarre exclusion of the signed statements, that the conviction was sound. I had not expected otherwise from a panel of reasonable and intelligent judges. It was always a slam dunk case.

I am not sure about this but I believe that Knox has been given 6o days in which to lodge an appeal, that is until the 8th October.

Friday, September 13, 2024

Florence Court Explains Second Knox Guilty Verdict For Criminal Slander #1

Posted by KrissyG

1. Overall Context

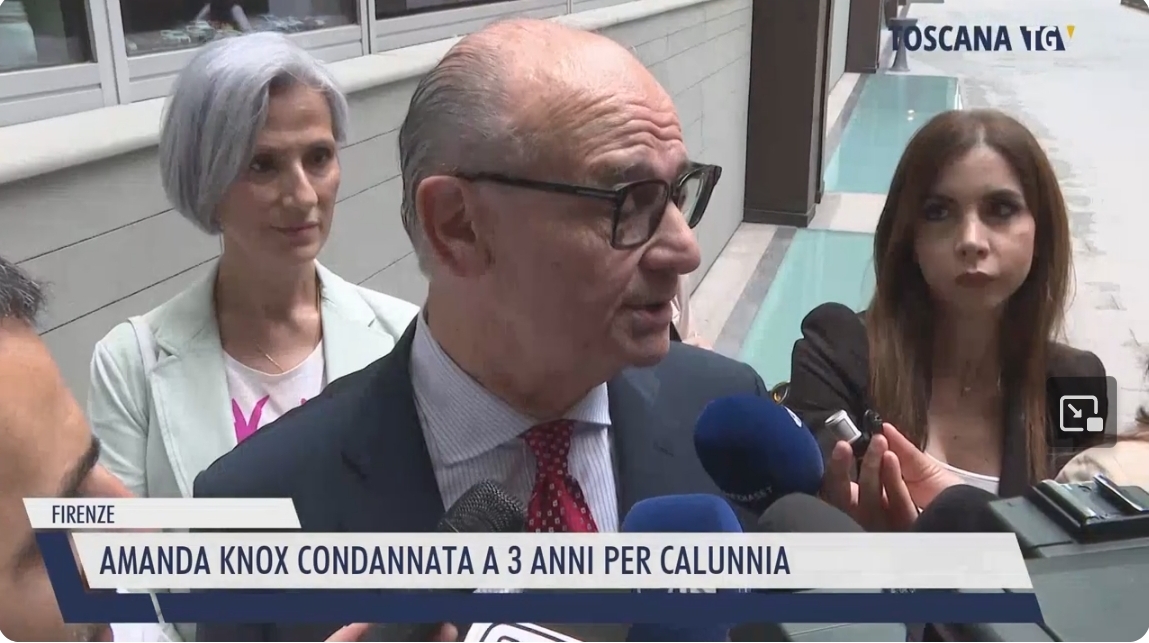

The image above shows Tuscany Chief Judge Nencini (left; 2014-15 lead judge on Knox’s main appeal) and Tuscany Appeals Court President Judge Anna Maria Sacco (second from right), the lead judge for this retrial, discussing another case.

This was Knox’s own repeat calunnia trial - a repeat of a segment of the 2009 trial. It was HER choice. It was not something Italy insisted upon. On this Knox had previously failed THREE appeals, in 2011, 2013, and (in part) 2015.

The option to request a new trial and potentially to wind back her felony conviction was offered to Knox (if she paid court costs if again found guilty) because of a bizarre and misinformed advisory to Italy from the European Court of Human Rights as we explain in earlier posts and again below.

Unlike the ECHR the Rome Supreme Court and Tuscany Appeal Court actually did their homework and now have seemingly left Knox without a leg to stand on.

Knox’s new guilty verdict was announced on 5 June by Judge Sacco. The long-form judges’ explanation (largely unique to Italy; the US and UK have no direct equivalent) signed by Judge Sacco followed several weeks ago. If there is an appeal route we don’t see it.

Our Wiki and two PMF forums and TJMK have a track record of great caution in translations, often requiring back-and-forths to Italy, and so a final English version is still several weeks away. Meanwhile this is a first of several overviews.

2. Immediate Wider Context

Back in June Knox turned up at the Florence Court with her entourage in tow, having “defaulted” (the court’s word) by skipping the “merits” hearing back in October 2023.

The press saw Knox’s attendance as a sign that maybe she could be acquitted. But the written reasons indicate that her attendance was not optional; it was to do with showing up as ordered by the court, and so the default was revoked.

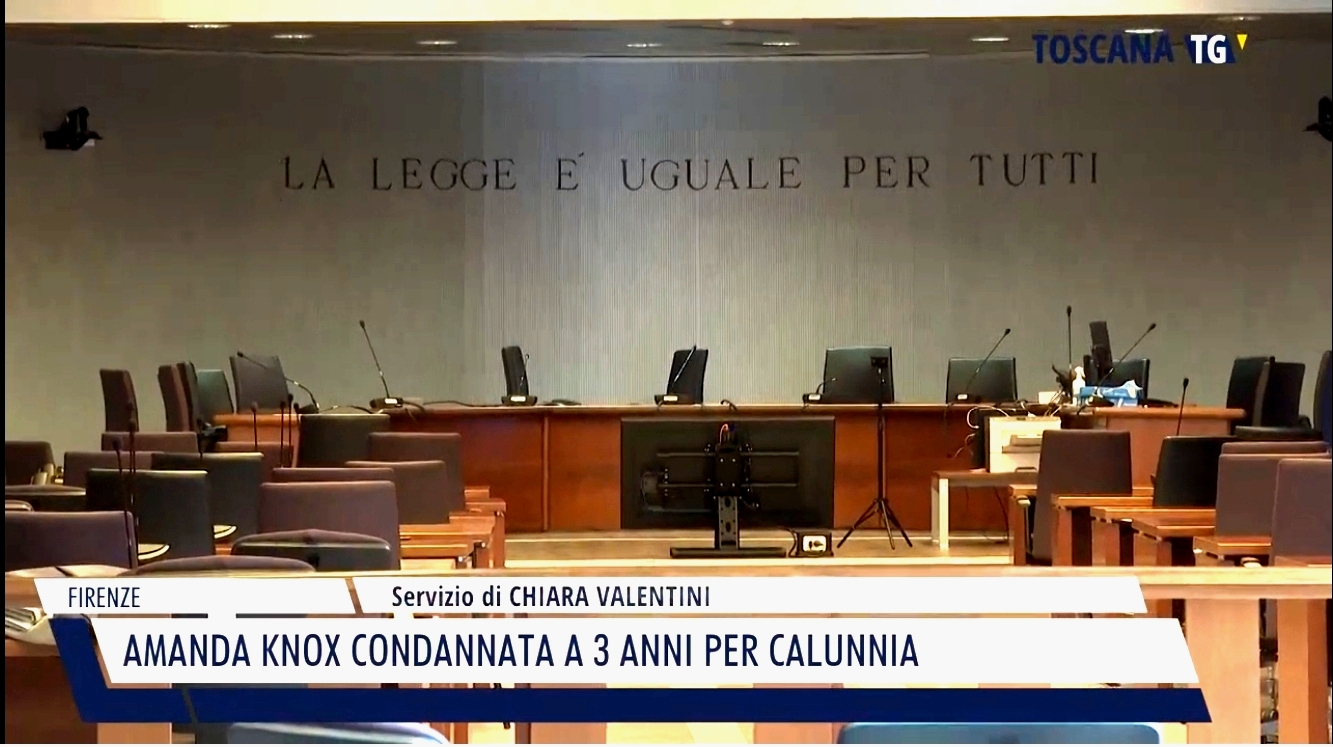

In the event, Knox declined to read out her ready prepared victory statement (though she later shared her delusional opening statement with the whole world) as the court ruled in Lumumba’s favour. It ordered that she pay an immediately enforceable €10,000 to him, plus the court costs. Her calunnia conviction was reinstated, with an amendment to one of the “aggravating” factors, as ruled on by the Fifth Chambers on 27 Mar 2015 (final verdict).

3. Immediate Narrow Background

The background of the retrial is that Knox’s defence had demanded the Calunnia conviction be quashed, owing to the ECHR finding of 24 Jan 2019, under Article 6, “right to a fair trial”, and in part Article 3, “freedom from psychological pressure”, that (a) a lawyer was not provided as of the times Knox made her verbal allegations against Patrick Lumumba, and that (b) the interpreter provided, Anna Donnino, had exceeded her remit in providing Knox emotional support (this is all the ECHR upheld; Knox had requested more, including a vast payment, but ECHR endorsed a mere token equivalent of $20,000).

To this the Florence Court now points out:

However, the Strasbourg Court did not find any infringement of Article 81 EC in substantive terms of the Convention, observing that there was “nothing to support the conclusion that the applicant had been subjected to the inhuman and degrading treatment complained of.”

The only remaining allowable evidence re the calunnia charge was the written document dated 6 Nov 2007, which Knox had hand-written around noon and gleefully handed to policewoman Ficarra as “a gift” after having provided two signed statements after midnight.

It was thus decided by the Central Court of Cassation (Supreme Court) on 10 Oct 2023 that the case could go back down to retrial, with the two typed and signed statements impermissible, and the remaining independently-written post-noon one assessed on its merits as to whether it could be said to be a case of Aggravated Criminal Calunnia against Lumumba.

“Aggravated” relates to a serious crime that attracts more than ten years imprisonment and accordingly:

... of teleological connection, ex art. 61 n. 2 cod. pen. for having acted in order to obtain impunity for all and, in particular, Guede Rudi Hermann for the crime of murder.

Knox was jailed for three years (2009-2011) for “multiple aggravated slander”, with some aggravating elements excluded by the Supreme Court Fifth Chambers final verdict of 27 March 2015.

The Supreme Court’s College of Legality had thus ruled that the convictions of 26 Mar 2013 and that of 27 March 2015 together with the Perugia Court of Appeal of 3 Oct 2011 – the controversial Hellmann court that saw Knox freed to fly back to America but still convicted of calunnia – could all be annulled conditional upon a retrial and possible re-conviction of calunnia albeit with time served.

Knox’s oral accusations against Lumumba had been made at around 01:00 and again at 05:45; these are the statements now barred as evidence because of the murky ECHR ruling. But Knox’s claimed ‘retraction’ was written in private and in English at circa 13:00, the same day.

The warrant executed for Lumumba’s arrest and subsequent imprisonment had been enacted at 08:30 that morning (6 Nov 2007) and thus precedes the timing of the memo in question.

4. The Defendant’s Case

Knox’s lawyers (Carlo Dalla Vedova of Rome and Luca Luparia Donati of Milan) argued thus:

... the memorial was a dream-like account of the fragments of a nightmare in which Amanda Marie Knox repeatedly admitted that she was unsure of having lived the confusingly reported experience, which re-emerged in the reality elaborated by her mind, badly prostrated after the last interrogation held the previous night. These were flashbacks which she herself doubted to the point of questioning who the real murderer was and of ruling out the possibility of being considered a witness against Diya Lumumba.

The Florence Appeal Court rejected this claim, reasoning that the language deployed was escamotage – a trick or sleazy ploy. For something to be considered circumstantial evidence, there needs to be a logical chain of events that leads up to it and from it.

The Appeal Court now points out that Knox’s use of the clear chain of events (seeing Patrick in the basketball court – seeing him at the door - hearing Meredith’s screams) couldn’t be claimed to be a “messy dream” in particular because the event of Meredith’s screaming had been independently witnessed and verified by two separate neighbours, and because Knox was the only person with the key to access the apartment that night.

5. The Civil Party’s Case

Carlo Pacelli of Perugia representing Patrick Lumumba argued as follows.

In this regard he highlighted the part of the writing in which Amanda Marie Knox claimed that she had not lied when she had said that she thought the killer was Patrick and added immediately afterwards “I really thought he was the murderer”.

6. Court Consideration Of Arguments

The defence for Knox claimed the memo represented a retraction of the claims she had made during the early hours and a need to clarify that she was doubtful and confused.

The Florence Court rejected this, saying that far from being a retraction or a description of a dream state, it was a reiteration, with the language used not as expressing doubt but as “a ploy” or a literary device if you like.

It explained that under the criminal code, a defendant was allowed to lie about their own involvement in a crime (equivalent to the right not to incriminate oneself), but, when an innocent third party is blamed, it brings in the concept of risk brought upon against that person.

Thus, Knox had endangered Lumumba with imprisonment and the risk of a conviction of a serious crime, of which he did unfairly serve fourteen days.

In its reasoning, the court further points out the transcripts of police wire-tapping of Knox talking in prison with her mother, in which she says she felt “terrible” about what she had done to Lumumba. Putting him “in a horrible situation and in jail through her fault, reiterating that concept several times”.

And yet, the court points out, Knox failed to mention Lumumba’s innocence at her post-arrest remand hearing with Magistrate Matteini, indicating a deliberate false accusation against Lumumba. (That was the hearing where for the second time Sollecito seriously sold Knox down the river. And as per routine procedure, Matteini now took over overall management of the case from Dr Mignin.)

The court also notes:

The defendant told her mother - who spoke of possible lies spread artificially by the mass media - “But it is stupid. I can’t say any more, because I know that I was there and I can’t lie about it, I have no reason to do it.” (bold is mine).

The defence had also argued that Knox’s further memo written before 1:00 pm on 6 Nov 2007 (four days after the murder, at the Questura) was done after the time of the order of detention of Lumumba, at 08:30 am, and thus, they argue, cannot be said to have caused his arrest, her earlier statements which caused this now not being permitted as evidence.

The court dismisses this point, stating:

On the other hand, for the offense of criminal slander to be capable of being characterized, it is only necessary that the false accusation contains in itself the necessary and sufficient information for the initiation of criminal proceedings against a person who is unequivocally and easily identifiable, as was certainly the case - both nominally and documentally - in the present case.

It rejects the claim Knox was confused and bringing up false memories because of the logical nature of the sequence of events she describes, as pointed out above.

In any case, I note, personally - not the court - a false memory typically occurs when a person suffers a traumatic event and is unable to remember what happened. Later, with the passing of time, one’s brain fills in the missing details to make sense of the forgotten parts, and these details may be false.

For a memory to be false, a traumatic event must have happened in the first place. For example, via early childhood abuse or a car crash. If Knox had never been at the cottage whilst Meredith was murdered, how could she have a false memory of it? It certainly wouldn’t qualify as a “false memory” in its conventional sense.

The court further writes:

To conclude this point, it must be added that - a fortiori - the essential and direct nature of the false accusation does not make it either absurd or unlikely and confirms its suitability to integrate the material element of the alleged crime.

In Knox’s read-out statement to the current hearing she said “I wanted the police to know that I was doing my best to cooperate.” But the Florence Court questions this:

It must be said that the crime of slander requires general intent, that is to say, the conscience and willingness to charge a person who is innocent of a crime, the reason for the false accusation being irrelevant (Cassation 2489 of 2000).

[snip]

Amanda Marie Knox was perfectly aware of Diya Lumumba’s innocence, as Patrick is known, from a number of elements.

The first is that the defendant was at the time of the murder of Meredith Kercher at the house and, therefore, she knew that there was no Diya Lumumba there.

The situation is clear from Knox’s own writing, which locates her inside the house, and reports a scream from Meredith (“I saw myself curled up in the kitchen with my hands over my ears because in my head I heard Meredith screaming”).

That harrowing scream, which in her account required her to press her hands to her ears and to curl up in the kitchen in an attempt not to hear it, was a fact that really happened and was clearly perceived by Capezzali Nara and Monacchia Antonella, two neighbors of the house, with dwellings located near the cottage of via della Pergola #7, who both heard her, deeming it anomalous and atrocious, so much so that they were shocked.

[snip]

Meredith Kercher’s harrowing scream, at the time of Knox writing the accusatory statement against Diya Lumumba in the noon 6 November memoriale, was an element unknown to investigators, and to anyone who could not hear it because they were not present in or near the house where the murder took place.

[snip]

That circumstance demonstrates - first - the presence of Amanda Marie Knox in the house where the homicide occurred, at the time when it occurred, a place where, moreover, she herself sits (“curled up in the kitchen with her hands over her ears”) and, secondly, that the defendant was perfectly aware of the innocence of Diya Lumumba, known as Patrick, who was certainly not in that house.

7. The Florence Court’s Conclusions

The persistence of this attitude marks a clear departure from any behavior aimed at cooperation with investigators, so often represented by the defense and by the defendant herself, most recently in her final statements.

In short, Amanda Marie Knox must be held liable for the crime of aggravated criminal slander within the meaning of Article 2(2) of Regulation No 40/94 subpart f of paragraph 368 of the penal code).

The judgment at first instance [2009] must, however, be reformulated in part, first, by considering the definitive exclusion of the aggravating teleological link by reason of the formation of the final judgment on Knox’s acquittal on the charge of participation in the murder of Meredith Kercher, handed down by the Court of Cassation on 27 March 2015, and, second, from the point of view of the penalty [actually adjusted slightly by Judge Hellman in 2011].

[There follows various court costs orders.]

Thus decided in Florence on 5/6/2024

Anna Maria Sacco, President

Angelo Grieco, Jury Manager

And six lay judges

Thursday, June 13, 2024

Knox Lie-A-Thon #4: How Myriad Past Lies About “Forced Confession” Are Sinking Her Now

Posted by FinnMacCool

Breaking news 20 December 2013. This post goes live just as the news breaks that it was Knox lawyer Carlo Dalla Vedova who filed these patently false claims against the justice system of Italy with the European Court.

1. “There would be no need for these theatrics.”

Amanda Knox has not been present for any part of her latest appeal [at the Nencini court] against her own murder conviction. Nevertheless, she has made two meretricious contributions to the proceedings.

First, on the day that the prosecution opened its presentation of the case against her, she announced that her lawyers had filed an appeal against her slander conviction to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). ECHR hears only allegations of human rights abuses, which must be reported within six months of the alleged incident (or within six months after all local avenues have been exhausted; in this case none has even been explored).

This out-of-date application to an inappropriate body in pursuit of a groundless allegation is therefore bound to fail.

Knox’s second publicity stunt came on the day that her own defense lawyers began their own presentation. She sent a five-page email in English and Italian, with grammatical mistakes in each language, protesting her innocence and affirming that the reason she is not present in the court is because she is afraid of it.

There are many comments that could be made about the email, but perhaps its most grievous legal error comes in the aside where she claims that the “subsequent memoriali (sic), for which I was wrongfully found guilty of slander, did not further accuse but rather recanted that false ‘confession’.”

That singular document does not recant her previous statements (“I stand by what I said last night”), but does contain further accusations against Patrick Lumumba (“I see Patrik (sic) as the murderer”), as well as seeking to cast suspicion on Sollecito (“I noticed there was blood on Raffaele’s hand”), and on an unnamed “other person”.

However, by claiming that she has been “wrongfully found guilty” on that charge of calunnia, she is refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the Italian Supreme Court, which has definitively found against her on that count, and also of the Hellmann appeal court (the only court to date that has not found her guilty of the main charge of murdering Meredith Kercher).

Dr Alessandro Crini presented the prosecution’s case on November 25th/26th 2013. It was not a particularly theatrical performance, but rather a very long summary of the many items of evidence against Sollecito and Knox.

The most theatrical element of the case so far has been when one of the defendants insisted that the judge should read out five vacuous pages of her email immediately before her own lawyers presented their case on her behalf.

This gives a certain dramatic irony to Knox’s claim “If the prosecution truly had a case against me, there would be no need for these theatrics”.

Such ironies appear to be lost on Knox, however, since she seems incapable of reading back over her own work for solecisms or contradictions. (In the email itself, for example, in consecutive sentences she writes: “I had no contact with Rudy Guede. Like many youth in Perugia I had once crossed paths with Rudy Guede.”)

One of the many errors she makes in the email is to put in writing some of the wild claims that she and/or her supporters have previously made regarding the witness interview she gave on the night of November 5th/6th 2007.

The purpose of the current post is to consider that interview in greater detail, using as source material primarily Knox’s memoir “Waiting to be heard” (2013) and Raffaele Sollecito’s memoir, “Honor Bound” (2013), abbreviated here to WTBH and HB respectively.

2. “When we got there they said I couldn’t come inside.”

Amanda Knox was not even supposed to be at the police station on the evening of November 5th, 2007. She should have been attending a candlelit vigil, in which Meredith Kercher’s friends, classmates and supportive well-wishers met at eight o’clock at Corso Vannucci to proceed through to the Duomo, carrying candles and photographs of the victim.

A friend of Meredith’s “a young Polish student” texted Amanda Knox to invite her to this vigil, but Knox had better things to do. (WTBH: 82) She accompanied Sollecito to his friend Riccardo’s house for a bite to eat (HB: 29) where she absent-mindedly strummed a ukulele. (WTBH:82)

Knox writes of the vigil: “I wanted to be there but the decision was made for me” because “Raffaele had somewhere else to be”. (WTBH: 82)

One consistent feature of her narrative is her refusal to accept responsibility for anything, including her failure to turn up for her murdered roommate’s vigil, but we should note also that the vigil (eight o’clock) and the dinner (nine o’clock) both take place within the timeframe of her supposed series of interrogations, which according to her email involved “over 50 hours in four days”.

By her own account, when she ignored the police’s request not to accompany Sollecito to the Questura and just came anyway, it was the first contact she had had with the police in well over 24 hours.

Let us consider what was happening in the early part of the evening of November 5th, 2007.

The police are at the station studying the evidence; Meredith’s friends are proceeding downtown with candles and photographs of the victim; and Knox is playing the ukulele at Riccardo’s house.

Far from taking part in a lengthy coercive interview, Amanda Knox had gone to her University classes as normal, had bumped into Patrick Lumumba, whom she would later accuse of Meredith’s murder, and had later skipped the vigil to have dinner with Sollecito. (WTBH:83)

Meanwhile, back at the Questura, the police could see that Raffaele Sollecito’s stories simply did not add up.

They therefore called Sollecito and asked him to come into the station for further questioning. They told him that the matter was urgent; that they wanted to talk to him alone; and that Amanda Knox should not accompany him. (HB: 29)

Sollecito responded that he would prefer to finish eating first. (The same meal is used as an excuse for not attending the vigil at eight o’clock, and for delaying their response to the police request at around ten.) By his own account, Sollecito resented being ordered what to do by the police (HB: 29), and so he finished eating, they cleared the table together, and Amanda Knox then accompanied him to the station. (HB:30; WTBH: 83)

Naturally the police were both surprised and disappointed to see her. Their civilian interpreter, who had worked flat out through the weekend accompanying not only Amanda Knox but also the rest of Meredith’s English-speaking friends, had gone home. The only person they were planning to speak to that night was Sollecito, and even he was late. According to Knox, the police were not expecting their interview with Sollecito to take very long:

When we got there they said I couldn’t come inside, that I’d have to wait for Raffaele in the car. I begged them to change their minds. (WTBH: 83)

The police were not prepared for an interview with Amanda Knox. They had asked her not to come, and they tried to send her away when she got there. It was late on a Monday evening and there were no lawyers or interpreters hanging around on the off-chance that someone might walk into the police station and confess.

However, that’s what happened. And it is on that basis that Amanda Knox is now claiming that the interview which she herself instigated was improperly presented by the police:

I was interrogated as a suspect, but told I was a witness. (Knox email, December 15, 2013)

But she wasn’t a suspect. In fact, she wasn’t even supposed to be there.

3. “Who’s Patrick?”

We will now examine Knox’s claim that “the police were the ones who first brought forth Patrick’s name” (Knox blog, November 25th, 2013).

She has already admitted in court that this is not true. In fact, it is clear from her own book that the police did not even know who Patrick Lumumba was, at that point.

If they had suspected him or anybody else, they would have brought them in for questioning, just as they had already questioned everyone else they thought might be able to throw some light on the case.

The police plan that evening was to question Sollecito in order to establish once and for all what his story was. They would perhaps have brought Knox back the following day (together with the interpreter) to see how far Knox’s story matched Sollecito’s. In the event, their plan was disrupted first because Sollecito delayed coming in, and second because when he finally arrived, he had brought Knox with him.

“Did the police know I’d show up,” Knox asks rhetorically, “or were they purposefully separating Raffaele and me?” (WTBH: 83) She does not offer a solution to this conundrum, but the answer is (b), as the patient reader will have noticed.

She thus turned up to the police station despite being expressly asked not to come. The police asked her to wait in the car and she refused, complaining that she was afraid of the dark. They allowed her inside.

Today, she might complain that she “was denied legal counsel” (Knox email, December 15th 2013) as she entered the Questura, but there was absolutely no reason for a lawyer to be present, since by her own account, all the police were asking her to do is go home.

Knox did not go home. According to WTBH, while Sollecito is in the interview room, she sits by the elevator, doing grammar exercises, phones her roommates about where to live next, talks to “a silver-haired police officer” about any men who may have visited the house (she claims to have first mentioned Rudy Guede at this point, identifying him by description rather than name) and does some yoga-style exercises including cartwheels, touching her toes and the splits.

It is at this point “somewhere between 1130 and midnight” that Officer Rita Ficarra invites Knox to come into the office so that they can put on record Knox’s list of all the men she could think of who might have visited the house.

Knox takes several pages (WTBH 83-90) to explain how she went from doing the splits to making her false accusation against Patrick Lumumba. Like much of her writing, these pages are confused and self-contradictory.

One reason for the confusion is that Knox is making two false accusations against the police, but these accusations cannot co-exist. First, she attempts to demonstrate that the police made her give the name of Patrick Lumumba. Second, she wants us to believe that Officer Ficarra struck her on the head twice.

This is denied by all the other witnesses in the room, and Knox did not mention it in her latest story about applying to ECHR. In her memoriale (WTBH: 97), she claims she was hit because she could not remember a fact correctly.

But in her account of the interview (WTBH: 88), Knox explains that Ficarra hit her because, the fourth time she was asked, “Who’s Patrick?”, she was slow in replying, “He’s my boss.” This is the exact opposite of not remembering a fact correctly. Knox is so keen to make both false charges against the police stick that she fails to notice that one contradicts the other.

Knox at least provides us with two fixed times that allow us to verify the start and finish times of the formal interview. It began at 1230, when Anna Donnino arrived to interpret, and ended at 0145 when Knox signed her witness statement.

Bearing in mind that this statement would have needed to be typed up and printed before she signed it, the interview thus took little over an hour, and was not the “prolonged period in the middle of the night” that her recent blog post pretends. (We might also remember that Knox’s regular shift at Le Chic was from 9 pm to 1 am, meaning that the interview began during her normal working hours.) (WTBH:31)

WTBH also flatly contradicts Knox’s own claim that her accusation of Lumumba was coerced by the police.

According to her own account, she first mentions her boss (although not by name) in the less formal conversation, before the interpreter’s arrival, telling the police : “I got a text message from my boss telling me I didn’t have to work that night.” (WTBH: 84)

The police appear to pay no attention to the remark (which undermines Knox’s argument that the police were pressing her to name Lumumba) but instead keep questioning her on the timings and details of what she did on the night of the murder. And Knox finds those details difficult either to recall or to invent.

Donnino arrives at half past midnight, and the formal interview begins.

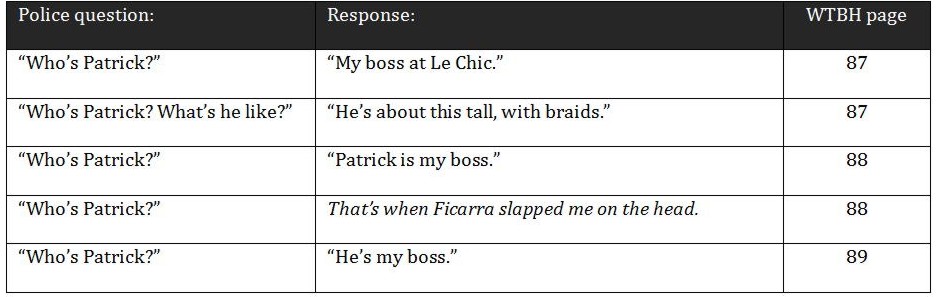

Again, the focus is on the timings of Amanda Knox’s movements on the night of the murder, and again she is having difficulty remembering or inventing them. Ficarra picks up Knox’s cell phones and observes: “You texted Patrick. Who’s Patrick?” and Knox answers, “My boss at Le Chic.” (WTBH: 86)

There is a short discussion about this text message, and then a second police officer asks her: “Who’s Patrick? What’s he like?” This time Knox answers: “He’s about this tall… with braids.” They then continue to discuss the text message, and then the police ask her a third time, “Who’s this person? Who’s Patrick?” Knox again replies: “Patrick is my boss.” (WTBH: 87)

Donnino then makes the intervention about how traumatic events can sometimes affect memory. Such events certainly seem to have an effect on the memory of the police, because one of them asks Knox a fourth time: “Who’s Patrick?” At this point, Knox claims in her memoir that Ficarra struck her on the head. (WTBH: 87)

This is nothing to do with failing to remember a fact correctly, because the fact is correct: Patrick Lumumba is indeed her boss.

The police continue to believe that she is hiding something, and they ask her who she is protecting. After a few minutes of questioning along those lines, Knox has an epiphany in which she claims that the face of Patrick Lumumba appeared before her and she gasps: “Patrick… it’s Patrick.”

If we believe one of Knox’s other stories, that the police were cunningly trying to get her to name Patrick Lumumba, we might expect them to be quite pleased to have succeeded at this point. But according to Knox, their response is to ask her a fifth time, “Who’s Patrick?” The whole room must have wanted to chorus at this point, “He’s her boss!”, but according to Knox, it is she herself who simply repeats: “He’s my boss.”

4. “I was also hit in the head when I didn’t remember a fact correctly”

Shortly after lunch on Tuesday November 6th, Knox wrote a piece of paper (known as her “memoriale”) in which she makes her first accusation that the police hit her. She hands this memoriale to Rita Ficarra, the very person she would later name as doing the hitting. We have noted above that in her account of the interview, the context Knox provides for this alleged blow is as follows:

This singularly repetitive catechism is supposed to have taken place at around one o’clock in the morning.

However, writing the following afternoon, Knox describes the event like this:

Not only was I told I would be arrested and put in jail for 30 years, but I was also hit in the head when I didn’t remember a fact correctly. I understand that the police are under a lot of stress, so I understand the treatment I received. (WTBH: 97)

This makes no sense as a reflection on the interview as she has earlier described it. In her version of the interview, she claims that the police kept asking her the same simple question, to which she keeps replying with the same factual answer, and the blows to the head take place in the middle of all that. Yet in her “memoriale”, she claims that the blow was because she could not remember a fact correctly.

In case two mutually contradictory accounts of that false allegation are not enough, Knox also provides a couple more explanations for why she was hit. Her third bogus claim is that the police said they hit her to get her attention, which makes for a dramatic opening to Chapter 10 of WTBH:

Police officer Rita Ficarra slapped her palm against the back of my head, but the shock of the blow, even more than the force, left me dazed. I hadn’t expected to be slapped.

I was turning around to yell “Stop!” my mouth halfway open, but before I even realized what had happened, I felt another whack, this one above my ear. She was right next to me, leaning over me, her voice as hard as her hand had been. “Stop lying, stop lying” she insisted.

Stunned, I cried out, “Why are you hitting me?” “To get your attention,” she said. (WTBH: 80)

This is a direct allegation against a named police officer, and not surprisingly it has resulted in another libel charge against Amanda Knox. It is a strong piece of writing, too: on its own, isolated from context, it reads like a trailer for the movie version. The trouble is, that when Knox later tries to set it in context, it makes no more sense than “because I didn’t remember a fact correctly” as an explanation as for why the blow came.

They pushed my cell phone, with the message to Patrick, in my face and screamed,

“You’re lying. You sent a message to Patrick. Who’s Patrick?”

That’s when Ficarra slapped me on my head.

“Why are you hitting me?” I cried.

“To get your attention,” she said.

“I’m trying to help,” I said. “I’m trying to help, I’m desperately trying to help.” (WTBH: 88)

This makes no sense. They already have Knox’s attention, and she is having no difficulty giving them a factual response to their repeated question, “Who’s Patrick?”

It is difficult to explain any logical motivation for that slap in terms of any of the three suggestions Knox has made so far: (1) because she couldn’t remember a fact correctly; (2) because she failed to answer the repeated question “Who’s Patrick?” quickly enough; or (3) to get her attention. She’d got the fact right, she’d answered the question, and they already had her attention.

Knox then provides us with a fourth version of possible reasons for the alleged slap. She describes the following encounter between herself and Rita Ficarra on their way to lunch at around two o’clock on Tuesday afternoon:

With my sneakers confiscated, I trailed [Ficarra] down the stairs wearing only my socks. She turned and said, “Sorry I hit you. I was just trying to help you remember the truth.” (WTBH: 94)

Once again, this makes no sense in the context of a blow to the head while waiting for a reply to the question, “Who’s Patrick?” It is perfectly true that Patrick Lumumba was Amanda Knox’s boss, and she had already correctly answered the same question twice, by her own account.

These are the four main WTBH versions of how Amanda Knox was struck on the head by Rita Ficarra. Perhaps she hopes that readers will choose the one they like best and will ignore its discrepancies with the others.

When testifying in court, however, Knox provided three further versions of the same alleged incident.