Category: Amanda Knox

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Knox’s Interrogation: A Major Contradiction Between Knox’s Book And Her Trial Testimony

Posted by James Raper

Amanda Knox now faces the prospect of not one but two trials where her claims in the book will become a real minefield to the defense and a major plus for the prosecutions.

If she goes back for the trials she may or may not get up on the stand, but either way she may blow it. If she doesn’t go back, she will indeed blow it in the eyes of the courts and it will be hard to escape guilty verdicts.

This post describes a particularly dangerous part of this minefield which seems quite certain to preoccupy both courts. It is about what actually happened on the 5th November 2007 when Amanda Knox was questioned at the central police station.

The police had called her boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito in to the station for questioning and Knox had accompanied him because she did not want to be alone. They had already eaten at the house of a friend of Sollecito’s.

Knox’s interrogation was not tape recorded and in that sense we have no truly independent account of what transpired. The police, including the interpreter, gave evidence at her trial, but we do not yet have transcripts for that evidence other than that of the interpreter. There are accounts in books that have been written about the case but these tend to differ in the detail. The police and the interpreter maintain that she was treated well. Apart from the evidence of the interpreter all we have is what Knox says happened, and our sources for this are transcripts of her trial evidence and what she wrote in her book. I shall deal with the evidence of the interpreter towards the end of this article.

I am going to compare what she said at trial with what she wrote in her book but also there was a letter she wrote on the 9th and a recording of a meeting with her mother on the 10th November which are relevant.. What she wrote in her book is fairly extensive and contains much dialogue. She has a prodigious memory for detail now which was almost entirely lacking before. I am going to tell you to treat what she says in her book with extreme caution because she has already been found out for, well let us say, her creative writing if not outright distortion of facts. I shall paraphrase rather than quote most of it but a few direct quotes are necessary.

Knox arrived with Sollecito at the police station at about 10.30 pm (according to John Follain). The police started to question Sollecito at 10.40 pm (Follain).

In her book Knox describes being taken from the waiting area to a formal interview room in which she had already spent some time earlier. It is unclear when that formal questioning began. Probably getting on for about 11.30pm because she also refers to some questions being asked of her in the waiting room following which she did some stretches and splits. She then describes how she was questioned about the events over a period from about the time she and Sollecito left the cottage to about 9 pm on the 1st November.

Possibly there was a short break. She describes being exhausted and confused. The interpreter, Knox says, arrived at about 12.30 am. Until then she had been conversing with the police in Italian.

Almost immediately on the questioning resuming -

“Monica Napoleoni, who had been so abrupt with me about the poop and the mop at the villa, opened the door. “Raffaele says you left his apartment on Thursday night,” she said almost gleefully. “He says that you asked him to lie for you. He’s taken away your alibi.””

Knox describes how she was dumfounded and devastated by this news. She cannot believe that he would say that when they had been together all night. She feels all her reserves of energy draining away. Then -

“Where did you go? Who did you text?” Ficarra asked, sneering at me.

“I don’t remember texting anyone.”

They grabbed my cell phone up off the desk and scrolled quickly through its history.

“You need to stop lying. You texted Patrick. Who’s Patrick?”

“My boss at Le Chic.”

Stop right there.

How were the police able to name the recipient of the text? The text Patrick had sent her had already been deleted from Knox’s mobile phone by Knox herself and Knox hasn’t yet named Patrick. In fact she couldn’t remember texting anyone.

It is of course probable that the police already had a log of her calls and possibly had already traced and identified the owner of the receiving number for her text, though the last step would have been fast work.

In her trial testimony Knox did a lot of “the police suggested this and suggestd that” though it is never crystal clear whether she is accusing the police of having suggested his name. But she is doing it here in her book and of course the Knox groupies have always maintained that it was the police who suggested his name to her.

The following extract from her trial testimony should clear things up. GCM is Judge Giancarlo Massei.

GCM: In this message, was there the name of the person it was meant for?

AK: No, it was the message I wrote to my boss. The one that said “Va bene. Ci vediamo piu tardi. Buona serata.”

GCM: But it could have been a message to anyone. Could you see from the message to whom it was written?

AK: Actually, I don’t know if that information is in the telephone”¦”¦”¦”¦”¦”¦”¦..

GCM : But they didn’t literally say it was him!

AK : No. They didn’t say it was him, but they said “We know who it is, we know who it is. You were with him, you met him.”

GCM : Now what happened next? You, confronted with the message, gave the name of Patrick. What did you say?”

AK : Well, first I started to cry…....

And having implied that it was the police who suggested Patrick’s name to her, she adds”¦.. that quote again -

“You need to stop lying. You texted Patrick. Who’s Patrick?”

“My boss at Le Chic.”

Here she is telling the Perugian cops straight out exactly to whom the text was sent. “My boss at Le Chic”.

But that does not quite gel with her trial testimony -

And they told me that I knew, and that I didn’t want to tell. And that I didn’t want to tell because I didn’t remember or because I was a stupid liar. Then they kept on about this message, that they were literally shoving in my face saying “Look what a stupid liar you are, you don’t even remember this!”

At first, I didn’t even remember writing that message. But there was this interpreter next to me who kept saying “Maybe you don’t remember, maybe you don’t remember, but try,” and other people were saying “Try, try, try to remember that you met someone, and I was there hearing “Remember, remember, remember…..

Doesn’t the above quote make it clear that the police were having considerable trouble getting Knox to tell them to whom her text message was sent? It would also explain their growing frustration with her.

But perhaps the above quote relates not to whom the text was sent but, that having been ascertained, whether Knox met up with that person later? Knox has a habit of conflating the two issues. However there is also the following quote from her trial testimony -

Well there were lots of people who were asking me questions, but the person who had started talking with me was a policewoman with long hair, chestnut brown hair, but I don’t know her. Then in the circle of people who were around me, certain people asked me questions, for example there was a man holding my telephone, and who was literally shoving the telephone into my face, shouting “Look at this telephone! Who is this? Who did you want to meet?”

Then there were others, for instance this woman who was leading, was the same person who at one point was standing behind me, because they kept moving, they were really surrounding me and on top of me. I was on a chair, then the interpreter was also sitting on a chair, and everyone else was standing around me, so I didn’t see who gave me the first blow because it was someone behind me, but then I turned around and saw that woman and she gave me another blow to the head.

The woman with the long hair, chestnut brown hair, Knox identifies in her book as Ficarra. Ficarra is the policewoman who started the questioning particularly, as Knox has confirmed, about the texted message. “Look at this telephone! Who is this? Who did you want to meet?” Again, surely this is to get Knox to identify the recipient of the text, not about whether she met up with him?

In the book though, it is all different.

In the book, the police having told her that the text is to someone called Patrick, Knox is a model of co-operation as, having already told them that he is her boss at Le Chic, she then gives a description of him and answers their questions as to whether he knew Meredith, whether he liked her etc. No reluctance to co-operate, no memory difficulties here.

Notwithstanding this, her book says the questions and insinuations keep raining down on her. The police insist that she had left Sollecito’s to meet up with - and again the police name him - Patrick.

“Who did you meet up with? Who are you protecting? Why are you lying? Who’s this person? Who’s Patrick?”

Remember again, according to her trial testimony the police did not mention Patrick’s name and Knox still hasn’t mentioned his name. But wait, she does in the next line -

“I said “Patrick is my boss.””

So now, at any rate, the police have a positive ID from Knox regarding the text message and something to work with. Patrick - boss - Le Chic.

Knox then refers to the differing interpretations as to what “See you later” meant and denies that she had ever met up with Patrick that evening. She recalls the interpreter suggesting that she was traumatized and suffering from amnesia.

The police continue to try to draw an admission from Knox that she had met up with Patrick that evening - which again she repeatedly denies. And why shouldn’t she? After all, she denies that she’s suffering from amnesia, or that there is a problem with her memory. The only problem is that Sollecito had said she had gone out but that does not mean she had met with Patrick.

Knox then writes, oddly, as it is completely out of sequence considering the above -

“They pushed my cell phone, with the message to Patrick, in my face and screamed,

“You’re lying. You sent a message to Patrick. Who’s Patrick?”

That’s when Ficarra slapped me on my head.”

A couple of blows (more like cuffs) to the head (denied by the police) is mentioned in her trial testimony but more likely, if this incident ever happened, it would have been earlier when she was struggling to remember the text and to whom it had been sent. Indeed that’s clear from the context of the above quotes.

And this, from her trial testimony -

Remember, remember, remember, and then there was this person behind me who—it’s not that she actually really physically hurt me, but she frightened me.”

In the CNN TV interview with Chris Cuomo, Knox was asked if there was anything she regretted.

Knox replied that she regretted the way this interrogation had gone, that she wished she had been aware of her rights and had stood up to the police questioning better.

Well actually, according to the account in her book, she appears to have stood up to the police questioning with a marked degree of resilience and self- certainty, and with no amnesia. There is little of her trademark “being confused”.

So why the sudden collapse? And it was a sudden collapse.

Given the trial and book accounts Knox would have us think that she was frightened, that it was due to exhaustion and the persistent and bullying tone of the questioning, mixed with threats that she would spend time in prison for failing to co-operate. She also states that -

(a) she was having a bad period and was not being allowed to attend to this, and

(b) the police told her that they had “hard evidence” that she was involved in the murder.

Knox has given us a number of accounts as to what was actually happening when this occurred.

In a letter she wrote on the 9th November she says that suddenly all the police officers left the room but one, who told her she was in serious trouble and that she should name the murderer. At this point Knox says that she asked to see the texted message again and then an image of Patrick came to mind. All she could think about was Patrick and so she named him (as the murderer).

During a recorded meeting with her mother in Capanne Prison on the 10th November she relates essentially the same story.

In her book there is sort of the same story but significantly without mention of the other officers having left the room nor mention of her having asked to see the texted message again.

If the first two accounts are correct then at least the sense of oppression from the room being crowded and questions being fired at her had lifted.

Then this is from her book -

In that instant, I snapped. I truly thought I remembered having met somebody. I didn’t understand what was happening to me. I didn’t understand that I was about to implicate the wrong person. I didn’t understand what was at stake. I didn’t think I was making it up. My mind put together incoherent images. The image that came to me was Patrick’s face. I gasped. I said his name. “Patrick””it’s Patrick.

It’s her account, of course, but this “Patrick - It’s Patrick” makes no sense at this stage of it unless it’s an admission not just that she had met up with Patrick but that he was at the cottage and involved in Meredith’s death.

And this is from her trial testimony -

GCM : Now what happened next? You, confronted with the message, gave the name of Patrick. What did you say?

AK : Well, first I started to cry. And all the policemen, together, started saying to me, you have to tell us why, what happened? They wanted all these details that I couldn’t tell them, because in the end, what happened was this: when I said the name of Patrick I suddenly started imagining a kind of scene, but always using this idea: images that didn’t agree, that maybe could give some kind of explanation of the situation.

There is a clear difference between these two quotes.

The one from her book suggests that she was trying hard but that the police had virtually brought her to the verge of a mental breakdown.

Her trial testimony says something else; that a scene and an idea was forming in her mind brought on by her naming of Patrick.

In her book she states that a statement, typed up in Italian, was shoved under her nose and she was told to sign it. The statement was timed at 1.45 am. The statement was not long but would probably have taken about twenty minutes to prepare and type.

The statement according to Knox -

... I met Patrick immediately at the basketball court in Piazza Grimana and we went to the house together. I do not remember if Meredith was there or came shortly afterward. I have a hard time remembering those moments but Patrick had sex with Meredith, with whom he was infatuated, but I cannot remember clearly whether he threatened Meredith first. I remember confusedly that he killed her.

The fact that the statement was in Italian is not important. Knox could read Italian perfectly well. However she does insinuate in the book that the details in the statement were suggested to her and that she didn’t bother to read the statement before signing.

Apart from what has been mentioned above, there are some other points and inferences to be drawn from the above analysis.

- 1. Knox’s account destroys one of Sollecito’s main tenets in his book Honour Bound. Sollecito maintains that he did nothing to damage Knox’s alibi until he signed a statement, forced on him at 3:30 am and containing the damaging admission that Knox had gone out. But Knox makes it clear that she had heard from the Head of the Murder Squad that he had made that damaging admission, at or shortly after 12.30 am. Or is Knox is accusing Napoleoni of a bare-faced lie?

2. It is valid to ask why Knox would not want to remember to whom the text had been sent. Who can see into her mind? Perhaps Knox realized that discussion of it would confirm that if she had indeed gone out then it was not to Le Chic, where she was not required. However even if she thought that could put her in the frame it’s not what an innocent person would be too worried about. Perhaps she did just have difficulty remembering?

3. If there was no fuss and she did remember and tell the police that the text was to Patrick, and the questioning then moved on to whether she met up with Patrick later that evening, what was the problem with that? She knew the fact that she hadn’t met up with him could be verified by Patrick. She could have said that and stuck to it. The next move for the police would have been to question Patrick. They would not have had grounds to arrest him.

4. Knox stated in her memorial, and re-iterates it in her book, that during her interrogation the police told her that they had hard evidence that she was involved in Meredith’s murder. She does not expand on what this evidence is, perhaps because the police did not actually tell her. However, wasn’t she the least bit curious, particularly if she was innocent? What was she thinking it might be?

5. I can sympathise with any interviewee suffering a bad period, if that’s true. However the really testy period of the interview/interrogation starts with the arrival of the interpreter, notification of Sollecito’s withdrawal of her alibi and the questioning with regard to the text to Patrick, all occurring at around 12.30 am. There has to be some critical point when she concedes, whether to the police or in her own mind, that she’d met “Patrick”, after which there was the questioning as to what had happened next. Say that additional questioning took 20 minutes. Then there would be a break whilst the statement is prepared and typed up. So the difficult period for Knox, from about 12.30 am to that critical point, looks more like about 35 to, at the outside, 50 minutes.

6. Even if, for that period, it is true that she was subjected to repeated and bullying questions, and threats, then she held up remarkably well as I have noted from her own account. It does not explain any form of mental breakdown, let alone implicating Patrick in murder. In particular, if Knox’s letter of the 9th and the recording of her meeting with her mother on the 10th are to believed, that alleged barrage of questions had stopped when she implicated Patrick. An explanation, for what it’s worth, might be that she had simply ceased to care any longer despite the consequences. But why?

7. A better and more credible explanation is that an idea had indeed formed suddenly in her mind. She would use the revelation about the text to Patrick and the consequent police line of questioning to bring the questioning to an end and divert suspicion from her true involvement in the murder of Meredith Kercher. She envisaged that she would be seen by the police as a helpless witness/victim, not a suspect in a murder investigation. As indeed was the case initially. She expected, I am sure, to be released, so that she could get Sollecito’s story straight once again. If that had happened there would of course remain the problem of her having involved Patrick, but I dare say she thought that she could simply smooth that over - that it would not be a big deal once he had confirmed that there had been no meeting and that he had not been at the cottage, as the evidence was bound to confirm.

At the beginning I said that we also have a transcript now of the evidence of the interpreter, Anna Donnino. I will summarise the main points from her evidence but it will be apparent immediately that she contradicts much of what Knox and her supporters claim to have happened.

Donnino told the court that she had 22 years experience working as a translator for the police in Perugia. She was at home when she received a call from the police that her services were required and she arrived at the police station at just before 12.30 am, just as Knox said. She found Knox with Inspector Ficarra. There was also another police officer there whose first name was Ivano. At some stage Ficarra left the room and then returned and there was also another officer by the name of Zugarina who came in. Donnino remained with Knox at all times

The following points emerge from her testimony :-

- 1. Three police officers do not amount to the “lots of people” referred to in Knox’s trial testimony, let alone the dozens and the “tag teams” of which her supporters speak.

2. She makes no mention of Napoleoni and denied that anyone had entered the room to state that Sollecito had broken Knox’s alibi. (This is not to exclude that this may have happened before Donnino arrived)

3. She states that Knox was perfectly calm but there came a point when Knox was being asked how come she had not gone to work that she was shown her own text message (to Patrick). Knox had an emotional shock, put her hands to her ears and started rolling her head and saying “It’s him! It’s him! It’s him!”

4. She denied that Knox had been maltreated or that she had been hit at all or called a liar.

5. She stated that the officer called Ivano had been particularly comforting to Knox, holding her hand occasionally.

6. She stated that prior to the 1.45 am statement being presented to Knox she was asked if she wanted a lawyer but Knox said no.

7. She stated that she had read the statement over to Knox in english and Knox herself had checked the italian original having asked for clarification of specific wording.

7. She confirmed that that she had told Knox about an accident which she’d had (a leg fracture) and that she had suffered amnesia about the accident itself. She had thought Knox was suffering something similar. She had also spoken to Knox about her own daughters because she thought it was necessary to establish a rapport and trust between the two of them.

The account in Knox’s book is in some ways quite compelling but only if it is not compared against her trial testimony, let alone the Interpreter’s testimony: that is, up to the point when she implicates Patrick in murder. At that point no amount of whitewash works. The Italian Supreme Court also thought so, upholding Knox’s calunnia conviction, with the addition of aggravating circumstances.

Sunday, May 12, 2013

With Diffamazione Complaint Against False Claims In Oggi Knox’s Legal Prospects Continue To Slide

Posted by Our Main Posters

[Above: the Palace of Justice in Bergamo where Knox and Sollecito might spend some time]

Knox’s public relations campaign is starting to look very, very odd.

As many of our recent posts have explained, no really good lawyer in Italy would ever allow their clients to put out an inflammatory book while their legal process is still going on. It hasn’t happened in any other Italian cases in years.

And now in this case it has happened twice.

Sollecito’s book reeked of blood money, arrogance and contempt, it twisted and discounted much of the evidence, made claims which both Sollecito and others had previously contradicted, made accusations of criminal behavior against officers of the court, and separated himself from Knox.

Now guess what?

Despite the fact that Sollecito’s book was promptly dispatched to the Florence and Verona chief prosecutors with diffamazione and vilipendio complaints, Knox’s book too reeked of blood money, arrogance and contempt, it too twisted and discounted much of the evidence, it too made claims which both Knox and others had previously contradicted, it too made accusations of criminal behavior against officers of the court, and it separated her from her co-perp.

In each case there was a shadow writer, respectively Andrew Gumbel and Linda Kulman, who seem to have tired early on of the clients, as all their hired help tends to do, and simply copied the FOA playbook into the books with no sources at all checked beyond that narrow group.

To cool-headed and informed people who really know the case, Gumbel’s sources were rather a joke. PR shills Nina Burleigh and Candace Dempsey and Steve Moore? Really? And Linda Kulman seems to have fallen into the same trap.

This becomes very obvious when you watch the two “authors” at their interviews. They are both hampered and tongue-tied because for the life of them neither can remember what their shadow writers put in the books. Several interviewers have actually caught them out.

As we knew the Bergamo lawsuit against Oggi and Knox was headed down the pike, we set out what we consider to be the state of play last Friday. It still stands up, but might be embellished just a bit.

First, here is Andrea Vogt’s helpful description of what’s in the Bergamo complaint..

The 8-page complaint is addressed to the Prosecutor’s Office in Bergamo (near Milan), where the headquarters of the magazine are located. It cites as slanderous the suggestion that Knox was illegally interrogated and maintains that there is no trial or investigation documentation supporting a number of “affirmations that were never made.” Mignini insists Knox was initially heard by him as a witness with key information relevant to the murder of Meredith Kercher, not as a suspect herself.

“Knox never asked for an attorney. She wanted to talk,” Mignini wrote, adding that he did not contest her statements or question her at that time, because she was making a spontaneous declaration regarding Patrick Lumumba’s alleged involvement. [In other words, not about herself.]

The complaint also questions allegations of prison mistreatment and indicates specific persons and neutral institutions as having knowledge on the matter, including the Capanne prison chaplain, U.S. embassy officials, center-right politician Rocco Girlanda and secretary general of the Italy-USA Foundation Corrado Daclon, all of whom visited Knox regularly in prison.

Also contested are phrases reported by Oggi and attributed to Knox’s memoir claiming he had a bizarre past that included a conviction on abuse of office charges that was pending appeal, when in fact he was fully and definitively acquitted of those charges in 2011 by a Florence court.

Italy’s high court (Cassation) recently agreed with his office’s request to re-open the Monster of Florence/Narducci case, the complaint notes. That decision has lent new credence to his long-running investigation of the suspicious 1985 death of a Perugian doctor who some investigators believe was involved (Italy’s Cassation Court in March also ordered Mario Spezi, co-author of the Monster of Florence bestseller, to stand trial for allegedly attempting to pin the blame on another man).

While the targets of the suit are stated to be Oggi and Amanda Knox and her publishers, the REAL target appears set to be the FOA playbook as set out in Amanda Knox’s book. And for that matter in Raffaele Sollecito’s book.

The first complainant (there are expected to be others) Giuliano Mignini has advanced a request for a formidable slate of witnesses, which could come to include even the lawyers for Sollecito and Knox.

Won’t that be fun. As they are interrogated on the stand, each witness is going to have to take a position on what crazy stuff the FOA have pushed into the books.

Did the prosecutor offer Sollecito an illegal deal or not? Did Knox get interrogated about Patrick by the prosecutor while denying her a lawyer or not? Did Knox complain to her lawyers about conditions in prison and if so why do those lawyers and so many others say she did not?

And maybe fifty more sudden-death choices like the above. Gee thanks Oggi and Amanda Knox. This could set some facts straight, in front of the whole world.

Demonizations By Knox: OGGI Charged For Article Conveying False Claims To Italy #2

Posted by Our Main Posters

[Umberto Brindani, editor of Oggi, a Mario Spezi ally, being sued for publishing Knox’s claims in Italy]

The decision of Amanda Knox and her lawyers and publishers to flaunt her dishonest claims in Italy seems seriously ill advised.

Pouring gasoline on the fames, it has opened up a fast-track way for those many who she nastily attacks to put the real truths in front of the world. Nobody who foolishly parrots her will be immune from being required to testify by the courts, her own lawyers included.

Here are our own short rebuttals of the Knox claims Oggi specifically flaunts to Italy in its unresearched review.

- Knox was NOT interrogated for days and nights. She was put under no pressure in her brief witness interviews except possibly by Sollecito who had just called their latest alibi “a pack of lies”.

- Knox WAS officially investigated in depth, after she surprisingly “confessed” and placed herself and Patrick at the scene. Prior to that she’d been interviewed less than various others, who each had one consistent alibi.

- Knox herself pushed to make all three statements without a lawyer on the night of 5-6 November 2007 in which she claimed she went out from Sollecito’s house, met Patrick, and witnessed him killing Meredith.

- Far from Knox being denied a lawyer, discussions were stopped before the first statement and not resumed, in the later hearing she was formally warned she needed one; she signed a confirmation of this in front of witnesses.

- Prosecutor Mignini who Knox accuses of telling her a lawyer would hurt her prospects when she claims she asked for one was not even in the police station at that interview; he was at home.

- She was not prohibited from going to the bathroom. At trial, she testified she was treated well and was frequently offered refreshments. Her lawyers confirmed this was so.

- She was not given smacks by anyone. Over a dozen witnesses testified that she was treated well, broke into a conniption spontaneously, and thereafter was hard to stop talking.

- There is no evidence whatsoever that Knox was subject to “something similar to torture” and as mentioned above only Sollecito applied any pressure, not any of the police.

- There is nothing “suicidal” about returning to Italy to defend herself at the new appeal. Sollecito did. She risks an international arrest warrant and extradition if she doesn’t.

- There is no proof except for her own claims of sexual molestations in prison; she is a known serial liar; and she stands out for an extreme willingness to talk and write about sex.

- Many people have testified she was treated well in prison: her own lawyers, a member of parliament, and visitors from the US Embassy were among them; she herself wrote that it was okay.

- She may have based her account on her diaries and “prodigious memory” but the obviously false accusation against the prosecutor suggests that much of the book was made up.

- The investigators had a great deal of evidence against Knox in hand, not nothing, and they were not ever faulted for any action; they helped to put on a formidable case at trial in 2009.

- “Police and Italian justice work with such incompetence, ferocity, and disdain for the truth” is contradicted by a very complete record prior to trial which was praised by the Supreme Court.

- Mr Mignini has NO bizarre past at all. He is widely known to be careful and fair. He would not have been just promoted to first Deputy Prosecutor General of Umbria otherwise.

- He was put on trial by a rogue prosecutor desperate to protect his own back from Mignini’s investigations; the Supreme Court has killed the trumped up case dead.

- There was nothing “mysterious” about Knox being taken to the crime scene to see if any knives were gone, but her wailing panic when she saw the knives was really “mysterious”.

- Knox never thought she was in prison for her own protection; she had signed an agreement at the 5:00 am interview confirming she did know why she was being held.

- Monica Napoleoni did not “bluff” that Sollecito had just trashed their joint alibi; he actually did so, because his phone records incriminated him; he agreed to that in writing.

- There was no crescendo of “yelling and intimidations that lasts from 11 at night until 5.45”. There were two relatively brief sessions. Knox did most of the talking, named seven possible perps, and drew maps.

- There was zero legal requirement to record the recap/summary interview, no recording has “gone missing” and many officers present testified to a single “truth” about what happened.

Demonizations By Knox: OGGI Charged For Article Conveying False Claims To Italy #1

Posted by Our Main Posters

The popular Italian magazine Oggi was sent a review copy of Knox’s book by somebody in the United States.

Oggi has been a frequent vehicle for the Knox entourage version of events, and it has carried a number of lurid pro-Knox splashes. The magazine has a long history of nasty jabs at prosecution and police who as career civil servants under unusually strong rules have no easy ways of explaining their side.

Like all of Oggi’s articles on the case, this shrill and foolish piece is totally one-sided and absolutely unresearched.

- Oggi is ignorant of the fact that many days of testimony by police officers at trial in 2009 contradict Knox’s book, highly convincing testimony, to which Knox on the stand had only the most feeble and unconvincing of responses.

- Oggi is ignorant of the fact that Judge Massei and even Judge Hellmann disbelieved her, and (in extensive reasoning) the Supreme Court (make sure to read parts 3, 7 and 15 there).

- Oggi is ignorant of the fact that Knox was sentenced to three years in prison for the criminal framing of Patrick, and that sentence was confirmed both by Judge Hellmann and the Supreme Court - in effect, unless new FACTS come to light, the truth is known and the case is closed.

The book is already (see next post) the subject of a lawsuit which was filed Friday in Bergamo, where Oggi has its headquarters. Knox is also expected to be investigated for contempt of court. Her book carries at least one no-contest false accusation of a crime: Knox claims the much respected Prosecutor Mignini illegally interrogated her without a lawyer and attempted to make her definitively accuse Patrick Lumumba. This is repeated below. In fact Mr Mignini was not even there.

This translation below of the Oggi piece is by our main poster Catnip. Passages that can EASILY be shown to be false (Oggi would have known they were false with a mere 3-4 hours of research) are highlighted here.

See our own rebuttals in this next post.

Amanda Knox: The American girl’s sensational story

Chilling. No other adjectives come to mind after having read Waiting to be Heard, finally released in the United States. An extremely detailed and very serious charge against the police and magistrates who conducted the investigation into the murder of Meredith Kercher.

Immediately after the crime, Amanda recounts, and for entire days and nights, they had interrogated the American girl and placed her under pressure to make her confess to a non-existent truth, without officially investigating her, denying her the assistance of a lawyer, telling her lies, even prohibiting her from going to the bathroom and giving her smacks so as to make her sign a confession clearly extorted with something similar to torture.

And now the situation is very simple. There are only two choices: either Amanda is writing lies, and as a consequence the police officers and magistrates are going to have to sue her for defamation; or else she is telling the truth, and so they are going to have to go, not without being sanctioned by the CSM [the magistrates’ governing body] and the top brass of the Police. The third possibility, which is to pretend that nothing has happened, would be shameful for the credibility of our judicial system.

Amanda Knox has written her Waiting to be Heard memoir with the sense of revulsion and of relief of someone who has escaped by a hair’s breadth from a legal disaster, but has got her sums wrong. Cassation has decided that the [appeal] proceedings have to be redone and the hearings should be (re)commencing in October before the Florence Court of Appeal.

In a USA Today interview, Ms Knox has not excluded the possibility of “returning to Italy to face this battle too”, but it would be a suicidal decision: it’s likely that the appeal will result in a conviction, and the Seattle girl will end up in the black hole from which she has already spent 1,427 days.

In this way Waiting to be Heard risks being the “film” on which Amanda’s last words are recorded about the Mystery of Perugia, her definitive version.

We have read a review copy. And we were dumbfounded. Waiting to be Heard is a diary that has the frenetic pace of a thriller, written in a dry prose (behind the scenes is the hand of Linda Kulman, a journalist at the Huffington Post), even “promoted” by Michiko Kakutani, long-time literary critic at the New York Times.

The most interesting part does not concern the Raffaele Sollecito love story (which Amanda reduces it to puppy love: “With the feeling, in hindsight, I knew that he… that we were still immature, more in love with love than with each other”), and whoever goes looking for salacious details about the three Italian boys Amanda had casual sex with, one night stands, will be frustrated (Ms Knox describes those encounters with the nonchalance of an entomologist disappointed with his experiments: “We undressed, we had sex, I got dressed again with a sense of emptiness”).

There are no scoops about the night of the murder and even the many vicissitudes endured during the 34,248 hours spent in Capanne prison - the [claimed] sexual molestations suffered under two guards, the unexpected kiss planted by a bisexual cellmate, the threats made by another two prisoners - remain on the backdrop, like colourful notations.

Because what is striking and upsetting, in the book, is the minute descriptions, based on her own diaries, on the case documents and on a prodigious memory, of how Ms Knox had been incriminated (or “nailed”).

COME IN KAFKA. A Kafkian account in which the extraordinary naivety of Amanda (the word naïve, ingénue, is the one which recurs most often in the 457 pages of the book) mixes with the strepitous wickedness of the investigators decided on “following a cold and irrational trail because they had nothing better in hand”.

Devour the first 14 chapters and ask yourself: is it possible that the Police and Italian justice work with such incompetence, ferocity, and disdain for the truth? You place yourself in her situation and you scare yourself: If it happened to me? You’re in two minds: is it a likely accusation, or a squalid calumny, the version of Amanda?

Because in reading it you discover that in the four days following the discovery of Meredith Kercher’s body (on 2 November 2007), Amanda was interrogated continuously, and without the least of procedural guarantees [=due process].

She changes status from witness to suspect without being aware of it.” No one had told me my rights, no one had told me that I could remain silent”, she writes. When she asked if she had the right to a lawyer, the Public Prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini, had responded like this: “No, no, that will only worsen things: it would mean that you don’t want to help us”. Thus, the Public Prosecutor, Giuliano Mignini.

For a long period of time, Ms Knox, who at the time spoke and understood hardly any Italian at all, mistook him for the Mayor of Perugia, come to the police station to help her.

Then, with the passage of time and of the pages, the assessment changes: Mignini is a prosecutor “with a bizarre past”, investigated for abuse of office (he was convicted at first instance, but Cassation annulled the verdict on the grounds of lack of jurisdiction: the case will be tried again in Florence) and with the hunger to fabricate “strange stories to solve his cases”.

Mignini “is a madman who considers his career more important than my liberty or the truth about the killing of Meredith”. On the phone, the Perugian prosecutor reacts with aplomb: “First I will read the book and then I will consider it. Certainly, if it really calls me “˜mad’ or worse, I think I will file suit”.

BEING IN PRISON IS LIKE CAMPING Amanda goes looking. When the officers mysteriously bring her along to the crime scene inspection of the apartment below the one in which she and Meredith were living in, Ms Knox put on the shoe protectors and the white forensics gloves and called out “ta-dah!” spreading her arms “as if I was at the start of a musical: I wanted to appear helpful”.

When they dragged her in handcuffs into Capanne Prison, she believed what the Police would have told her, and that was they would hide her for a couple of days to protect her (from the true killer, one presumes) and for unspecified bureaucratic reasons. “In my head I was camping: ‘This won’t last more than a week in the mountains’ I told myself” writes Amanda.

They take her money off her, and her credit cards, licence [?] and passport, and she draws strength from repeating to herself that “surely they’re not going to give me a uniform, seeing that I’m a special case and that I’ll be here for only a little while”.

But it’s the account of the notorious interrogation that takes the breath away. Around ten in the evening on her last day of freedom, Ms Knox accompanies Raffaele to the police station (he was called in, also without a lawyer, by the Police) and is thrown into a nightmare which she populates with many faces: there is Officer Rita Ficcara, who gives her two cuffs on the head (“To help you remember” she would say); there’s another officer who advises her: “If you don’t help us, you’ll end up in prison for 30 years”; Mignini arrives and advises her not to call a lawyer; super-policewoman Monica Napoleoni dives in and bluffs: “Sollecito has dropped your alibi: he says that on the night of the murder you had left his apartment and that you had told him to lie to ‘cover you’ “.

And a crescendo of yelling and intimidations that lasts from 11 at night until 5.45 in the morning. Seven hours “produce” two confessions that, exactly because they are made without a defence lawyer, cannot be used in the proceedings, but forever after “stain” the image of the accused Knox: Amanda places herself at the scene of the crime and accuses Patrick Lumumba.

RAFFAELE CONFIRMS THE ACCUSATIONS An account of the horror is confirmed by Sollecito in his memoir, Honor Bound, Raffaele writes of having heard “the police yelling at Amanda and then the cries and sobs of my girl, who was yelling “Help!” in Italian in the other room, and of having being threatened in his turn (“If you try to get up and go, I’ll punch you till you’ll bleed and I’ll kill you. I’ll leave you in a pool of blood”, another officer had whispered to him).

Published lines which have passed right under the radar of the Perugian investigators: “No legal action [against the interrogators] has been notified to us,” Franco Sollecito, Raffaele’s dad, tell us. For having recounted the sourness of her interrogation in court, Amanda was investigated for calunnia: the trial will take place in Florence. This one, too, will be a circumstantial case: it’s the word of two young people against that of the public prosecutor and the police.

The recording of the interrogation would have unveiled which side the truth stands on. But it has gone missing.

See our own rebuttals in this next post.

Below: images of the 4-page Oggi spread. Click for larger versions to read.

Thursday, May 09, 2013

Demonizations By Knox: She Invents An Illegal Interrogation By Mignini That Never Took Place

Posted by Our Main Posters

[The Perugia Central Police Station where Knox’s imaginary interrogation “took place”]

It is hard to imagine a more extreme form of contempt of court than Knox falsely accusing a respected prosecutor of interrogating her without her lawyer being present, and pressing her to incriminate others.

For this alone, Knox will certainly be investigated and charged. No wonder she is “scared” of returning to Italy. Apart from fears of getting up on the stand, she has lied about and falsely accused way too many people there.

1. What actually happened at Knox’s witness and suspect interviews:

Here is the true account, which has many witnesses, and then her account in the book, which has none.

Before 3:00 AM on 6 November 2007 the respected senior prosecutor Giuliano Mignini had barely set eyes on Amanda Knox.

At that point in time, she had just passed through a purely voluntary witness questioning with the police, who were actually much further ahead in questioning Sollecito and Knox’s flatmates and Meredith’s English friends.

Dr Mignini was at home asleep, but on call if the central police station needed him that night, which is how quite by chance he came face to face with Knox not long before dawn.

Knox’s latest alibi had just been collapsed in another witness interview room. Sollecito had collapsed their joint alibi almost instantly when shown phone records that proved he had just lied. He then declared their current alibi to be a pack of lies.

Told of this, Knox then floundered for a new explanation, turning finally to fingering her employer Patrick Lumumba who the police did not even know to exist until her phone record showed he did.

Police took down that statement, Knox signed it, and this at 3:00 am was the state of play.

Knox was in a waiting room and not under arrest. Mignini was required to warn Knox of her rights as a new suspect, and to warn her to do no further talking to him or anyone else around without a lawyer present.

This was especially so as Knox was inclining to babble on and on and officers were trying to calm her down. As the police had just found (and as her own lawyers later found) she can prove very difficult to stop.

This relatively brief meeting (in which Mignini made quite clear who he was, witnesses confirm) was extended to allow Knox to fine-tune her accusation of Patrick.

She shrugged off the right to have her lawyer there. Prior to this, Knox to Mignini was simply one of a whole lot of people who might be of interest, nothing more.

2. Knox’s invented version of the witness interview which never happened

This interrogation quoted from Knox’s book below is already attracting serious attention in Italy. Why? Because its just not her babbley tone, and because it never even took place.

Amanda Knox, Waiting To Be Heard, HarperCollins, Pages 90-92

[Description is of the end of Knox’s voluntary witness interview with police which Mignini did not attend; the most damaging claims are in bold]

Eventually they told me the pubblico ministero would be coming in.I didn’t know this translated as prosecutor, or that this was the magistrate that Rita Ficarra had been referring to a few days earlier when she said they’d have to wait to see what he said, to see if I could go to Germany.

I thought the “public minister” was the mayor or someone in a similarly high “public” position in the town and that somehow he would help me.

They said, “You need to talk to the pubblico ministero about what you remember.”

I told them, “I don’t feel like this is remembering. I’m really confused right now.” I even told them, “I don’t remember this. I can imagine this happening, and I’m not sure if it’s a memory or if I’m making this up, but this is what’s coming to mind and I don’t know. I just don’t know.”

They said, “Your memories will come back. It’s the truth. Just wait and your memories will come back.”

The pubblico ministero came in.

Before he started questioning me, I said, “Look, I’m really confused, and I don’t know what I’m remembering, and it doesn’t seem right.”

One of the other police officers said, “We’ll work through it.”

Despite the emotional sieve I’d just been squeezed through, it occurred to me that I was a witness and this was official testimony, that maybe I should have a lawyer. “Do I need a lawyer?” I asked.

He said, “No, no, that will only make it worse. It will make it seem like you don’t want to help us.”

It was a much more solemn, official affair than my earlier questioning had been, though the pubblico ministero was asking me the same questions as before: “What happened? What did you see?”

I said, “I didn’t see anything.”

“What do you mean you didn’t see anything? When did you meet him?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Where did you meet him?”

“I think by the basketball court.” I had imagined the basketball court in Piazza Grimana, just across the street from the University for Foreigners.

“I have an image of the basketball court in Piazza Grimana near my house.”

“What was he wearing?”

“I don’t know.”

“Was he wearing a jacket?”

“I think so.”

“What color was it?”

“I think it was brown.”

“What did he do?”

“I don’t know.”

“What do you mean you don’t know?”

“I’m confused!”

“Are you scared of him?”

“I guess.”I felt as if I were almost in a trance. The pubblico ministero led me through the scenario, and I meekly agreed to his suggestions.

“This is what happened, right? You met him?”

“I guess so.”

“Where did you meet?”

“I don’t know. I guess at the basketball court.”

“You went to the house?”

“I guess so.”

“Was Meredith in the house?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Did Patrick go in there?”

“I don’t know, I guess so.”

“Where were you?”

“I don’t know. I guess in the kitchen.”

“Did you hear Meredith screaming?”

“I don’t know.”

“How could you not hear Meredith screaming?”

“I don’t know. Maybe I covered my ears. I don’t know, I don’t know if I’m just imagining this. I’m trying to remember, and you’re telling me I need to remember, but I don’t know. This doesn’t feel right.”

He said, “No, remember. Remember what happened.”

“I don’t know.”At that moment, with the pubblico ministero raining questions down on me, I covered my ears so I could drown him out.

He said, “Did you hear her scream?”

I said, “I think so.”My account was written up in Italian and he said, “This is what we wrote down. Sign it.”

To repeat, Mignini was not even present at the midnight interrogation of Knox by the police, and he certainly never edged her into fingering Lumumba as is being claimed here. Knox herself did that all by herself in the presence of the police.

And she did it again and again. Emphatically.

[Dalla Vedova and Ghirga: did they illegally allow Knox to commit serious felonies in the book?]

Saturday, May 04, 2013

Knox Book - What The Newly Published Writings Reveal To Professional Eyes (1)

Posted by SeekingUnderstanding

Amateurism run amoke is what the unprecedented and unwise Knox extravaganza is starting to look like.

Several TJMK posts below this one have already suggested that the book was rushed into print with very little fact-checking, with no restraint on damaging false accusations, and with no strategic legal considerations.

The same thing seems to have happened with the TV appearances.

Knox had a year and a quarter under wraps to prepare herself and yet her many exaggerated and over-emotional TV claims contradict many things SHE HERSELF has said previously.

She seems to have been rehearsed by handlers with little or no grasp of the extensive fact record.

And where has all this amateurism left her? Open to slow erosion of her credibility by an increasing number of commentators while considerably upping her peril in Italy.

Because many of her claims falsely accuse officers of the court, she could be further indicted for contempt of court, and she could see the five years which was lopped off her sentence by Judge Massei for “mitigating circumstances” reinstated.

Those of us with psychology credentials may not have all been expecting the same thing from Knox when she finally surfaced. But none of us expected to be confronted so forcefully with a classic case of a personality in turmoil.

My first impression after getting through to the end of the book was that it shows such serious disturbance psychologically, so much being revealed in her own words.

It wouldn’t be possible to classify AK as clinically insane, the niceties of this being so precise - but an abnormal mind is clearly illustrated. So clear that it is actually sad - that she has been allowed and encouraged to do this.

The ghost writing, or/and her own expression is also painful to read in terms of quality of writing. These are the main points that have emerged for me, from a psychological perspective, after reading:

AK’s grip on reality (even without drugs) is tragically lacking. It seems that she doesn’t know what a ‘fact’ is. Every fact and event is seen through a lens of her own feeling or emotion - logical connection being absent - together with how she believes it is best to make it appear.

‘Her “best truth” is this over and over again. She doesn’t even understand that this is considered by normal minds to be lying. She doesn’t seem to have a concept of lying.

- “their version of reality was taking over”... Does reality only come in versions?

- “something didn’t feel right. it seemed made up”. Does she not know?

AK continually refers to herself as “different”. She is, but not for the curious or trivial things she believes. She is also obsessively concerned to be seen and classified as a “good person”. This comes up over and over.

“I didnt want them to think I was a bad person”. Note, not: “I didn’t want to BE a bad person” but always “how will people think of me”. This is a continual theme. “I couldn’t believe anyone could think that of me”.

It does show a dissociative and non-integrated personality, with both deep roots and serious implications. There are also indications that she is unable to ‘read’ people’s faces /expressions with any accuracy. (Emotion recognition).

A more sinister and disturbing facet to her personality connected to the above, which comes through in every chapter, is the automatic disparagement of anyone who displeases her (which of course happens frequently - whenever, in fact, someone has a different version to ‘her best truth’).

Someone is then ‘useless’, ‘betraying me’, ‘stupid’, etc etc. These words are all said matter-of-factly…. as if they really are facts. Here are some more of these words, peppered within the text:

- ‘Repellant, self-serving’, ‘hostile’, ‘insincere’, ‘abandoned (me)’, ‘uninterested’, ‘aggressive’, ‘spiteful’, ‘curt’, ‘disdainful’

- ‘Old perv…lecherous’, ‘glared cruelly’, ‘idiotic’, ‘insidious’, ‘controlling’, ‘condescending’, ‘mean’, ‘hateful’, ‘ruthless’....

Note that it is not that AK finds these people to be these things, in her opinion- it is that they ARE these things.

The sub-text is: I am a good person, and they, having displeased or disagreed with me, are ‘bad’. Thus the mechanism for strong, unrestrained projection is at work.

Example: “The police couldn’t bear to admit they were wrong.” Could she, though?

Her projections are so blatant, that I quake for her lack of self-awareness. I used to read literature as a window into self-awareness, insight, philosophical depths, and questions of morality.

Sadly this book is about as far from offering these as one could go. A PR machine missile is not a ‘book’ in the sense I used to know.

AK reveals a very strong inner anger, the control of which is difficult, and which it would seem she is frightened of, and frightened of revealing.

She would also seem to be based in a passive aggressive stance, which gives rise to a side seen as nice and even gentle. These two sides seem badly split.

This would be in keeping with the Envy hypothesis (I refer to Melanie Klein’s ‘Envy and Gratitude’). There are a few definite examples of the consuming anger which Amanda herself describes graphically.

She continually justifies it, also. Sometimes, of course, anger may be justified (‘just anger’) but as described here it is nearer to a rage or a tantrum when things aren’t going according to how she wants them to.

This speaks of manipulation, which would be part of the same profile, and is essentially destructive and spoiling, as well as something that wells up with a will of its own.

She often exposes her state of mind in certain phrases, without realising the implications of what she is saying. This is why I think the whole thing is so sad, as she has been used (seemingly mainly for money) in this foolish venture.

For example: “In that instant I snapped.” when the detective said “you know who killed Meredith.” It wasn’t the pressure/abuse from the police that made her snap, it was being confronted with the truth.

NOT her ‘best truth,’ but one that was simply unbearable to hear. There are many other examples, littered throughout the book, of some of her inner chaos:

- “This is my own fault. I caused the confusion”

- “I wanted to disappear. I didn’t want to be me anymore”.

- “I didn’t know if I was allowed to keep my thoughts private…”

- “Like a roller coaster ride….can’t get off. This is all my own fault” .

- ” I was furious for putting myself in this situation”.

- Rafaelle - “He didn’t look at me. I wondered if he hated me”. (Why should he?)

- “We want justice. But against who? We all want to know, but we all don’t.”

There are many others. Amanda Knox said she loved Italy and I believe her. With adjustment she could have been a lot happier there than she perhaps ever was in Seattle. Now she is in the position of demonizing Italy and its good people there, and in the worst possible way.

Italy was in fact very kind to Amanda Knox, and her treatment there was on the right lines to give her hope of enduring stability. What a pity that dirty PR and legal tricks and money grubbing may have pushed that out of sight forever.

Friday, May 03, 2013

The Amanda Knox Book: Good Reporters Start To Surface Amanda Knox’s False Claims In Droves

Posted by Our Main Posters

[American Ambassador to Italy David Thorne whose reports contradict Knox’s prison claims]

Did ANYBODY think to check Knox’s book for criminal defamations and false claims? Take this glaring “mistake” from page 248.

During the rebuttals, on December 3, each lawyer was given a half hour to counter the closing arguments made over the past two weeks. Speaking for me, Maria criticized Mignini for portraying Meredith as a saint and me as a devil

Really? Prosecutor Mignini said that? So why did the entire media corps report that it was said by Patrick Lumumba’s lawyer Carlo Pacelli? As the BBC reported:

[Mr Pacelli] added: “Who is the real Amanda Knox? Is it the one we see before us here, simple water and soap, the angelic St Maria Goretti?”

“Or is she really a she-devil, a diabolical person focused on sex, drugs and alcohol, living life to the extreme and borderline - is this the Amanda Knox of 1 November 2007?”

So even Mr Pacelli didnt compare Knox to Meredith, or simply call Knox a she-devil to her face. He asked rhetorically if she was a she-devil or a saint. Not exactly unheard of in American courts.

And remember he was addressing someone who would have been quite happy to see Patrick put away for life, cost him two weeks in a cell, entangled her own mother in a cover-up, destroyed Patrick’s business and reputation world-wide, still hasnt paid him money owed, and for lying about him served three years.

Prosecutor Mignini in fact never called Knox anything at all. We can find no record that he did. Again and again he has denied it. And he had no personal need to prosecute Knox, and certainly no need to frame her, despite many pages Knox devotes to trying to prove the reckless claim that he did.

Another false claim: Knox’s claim that Prosecutor Mignini invented the notion of a satanic cult to explain the Monster of Florence murders, also made by Sollecito, is totally untrue.

Dozens of others had suspected and talked about a satanic cult for YEARS before he investigated one loose end in the case. And both that theory and that investigation are back on track - at the recent order of the Supreme Court.

Another false claim: Knox devotes pages to trying to make herself look good on the witness stand at the trial. But Italians who could follow in Italian in real-time ended up suspecting and despising her performance up there. Read what they saw here and here.

Inspired by such conspicuous false claims as these, various reporters have begun to dig. We posted on Knox’s false claims about her prison time and the many disproofs. Italy-based reporter Andrea Vogt uncovers some more.

Knox’s memoir is a vivid personal account of the difficulties of prison life in Italy, complete with claims about inappropriate behaviour by staff. But Knox herself once painted a different picture.

Other documents - including writings Knox penned in her own hand while incarcerated, case files and state department records - conjure up quite another impression of a very different Knox, one who was more sanguine about her experience.

On the attitudes of the prison staff

“The prison staff are really nice,” wrote Knox in her personal prison diary, which was eventually published in Italy under the title Amanda and the Others.

“They check in to make sure I’m okay very often and are very gentle with me. I don’t like the police as much, though they were nice to me in the end, but only because I had named someone for them, when I was very scared and confused.”

She described Italian prisons as “pretty swell”, with a library, a television in her room, a bathroom and a reading lamp. No-one had beaten her up, she wrote, and one guard gave her a pep talk when she was crying in her cell.

Unlike the heavily-edited memoir, these are phrases she handwrote herself, complete with strike-outs, flowery doodles, peace signs and Beatles lyrics.

On the positive HIV result she was given

Both accounts also refer to the devastating but erroneous news from the prison doctor that she had tested positive for HIV, although her diary presents a more relaxed person at this point. “First of all, the guy told me not to worry, it could be a mistake, they’re going to take a second test next week.”

We also know that it was Knox’s own lawyers who leaked the HIV report and list of sex partners. Not the doctor or anyone else. No malice was intended, that is clear, despite her claims.

On her framing of her kindly employer Lumumba

[Knox] writes that she had a flashback to the interrogation, when she felt coerced into a false accusation. “I was weak and terrified that the police would carry out their threats to put me in prison for 30 years, so I broke down and spoke the words they convinced me to say. I said: ‘Patrick - it was Patrick.’”

In her memoir, she describes in detail the morning that she put that accusation in writing, and says the prison guard told her to write it down fast.

Yet in a letter to her lawyers she gives no hint of being rushed or pressured. “I tried writing what I could remember for the police, because I’ve always been better at thinking when I was writing. They gave me time to do this. In this message I wrote about my doubts, my questions and what I knew to be true.”

On her medical examination after arrest

“After my arrest, I was taken downstairs to a room where, in front of a male doctor, female nurse, and a few female police officers, I was told to strip naked and spread my legs. I was embarrassed because of my nudity, my period - I felt frustrated and helpless.”

The doctor inspected, measured and photographed her private parts, she writes - “the most dehumanising, degrading experience I had ever been through”.

But in the 9 November letter to her lawyers, she described a far more routine experience.

“During this time I was checked out by medics. I had my picture taken as well as more copies of my fingerprints. They took my shoes and my phone. I wanted to go home but they told me to wait. And that eventually I was to be arrested. Then I was taken here, to the prison, in the last car of three that carried Patrick, then Raffaele, then me to prison.”

On her persona and mood swings in prison

She says she was often suicidal, but recollections of prison staff and other inmates differ. Flores Innocenzia de Jesus, a woman incarcerated with Amanda in 2010 described Knox as sunny and popular among the children who were in Capanne with their mothers, and recalled her avid participation in music and theatrical events. She also held a sought-after job taking orders and delivering goods to inmates from the prison dispensary.

“Most of the time when we spoke during our exercise break, the kids would call her and she would go and play with them,” de Jesus told me.

And on what US officlals and her own lawyers perceived

State department cables, released through the Freedom of Information Act, show that between 2007 and 2009, three different high-level diplomats from Rome (Ambassador Ronald Spogli, Deputy Chief Elizabeth Dibble and Ambassador David Thorne) were among those reviewing Knox’s case.

Embassy officials visited regularly. Records show one consular official visited Knox on 12 November, soon after her arrest. A few weeks later she wrote in her diary how the visits of embassy officials improved her experience….

In 2008 and 2009, she was visited by two embassy officials at a time, six times. Ambassador David Thorne, whose name appears at the bottom of cables in August, November and December of 2009, is the brother- in-law of US Secretary of State John Kerry (at that time chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee).

If the diplomats knew anything of the “harrowing prison hell” Knox was going through (as one paper put it), they are keeping those reports under wraps. Neither Kerry nor any other prominent US politician has made any public complaints. Even today, her Italian lawyers maintain she was not mistreated.

Half a dozen obvious false claims and defamations here. We estimate we will uncover well over one hundred more.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Knox Book Put On Hold In UK As Legal Implications Of Blood Money For Still-Accused Finally Sink In

Posted by Our Main Posters

There have always been several huge problems in the promotion of Amanda Knox.

One problem is that Knox is not the real victim in the case and a great deal of compassion still resides for Meredith. Earning windfall blood money from the cruel death of a claimed close friend is hardly a classy way to go.

A second problem is that we are still only at the end of the second act of a three act play in terms of the trials and appeals, and the Italian Supreme Court in the third act to come will almost certainly be no gullible pushover. And a whining or inaccurate book or movie demonising Italy and Italians (as her complaints about Capanne already have done) might not help her legal prospects one little bit.

A third problem is that Italy’s officialdom and its population tend to maintain a hard and unblinking belief in the evidence against Sollecito and Knox, especially as the million dollar PR campaign largely flew below the radar there and they saw much of the hard case and a callous Knox live on TV. For example in Florence and Milan....

*******

Guess when we first posted those paragraphs above? Actually we posted them fifteen months ago on 6 January 2012.

And finally today fifteen months later HarperCollins UK suspended their publication of Knox’s book. Can the HarperCollins US suspension of the book be far behind?

We are not particularly given to directing legal advice to Amanda Knox - we think she should rethink and answer all the open questions - but the leeching of Knox-Mellas blood money going back nearly five years is absolute anathema to Meredith’s family.

So we have posted five subsequent times, pointing out to the Knox-Melasses and Robert Barnett and Ted Simon what should have been very, very obvious to them when they did their due diligence in Italy on the book:

Publishing to impugn Italian justice officials while still accused in an ongoing legal process is a contempt of court felony in Italy.

Ask Raffael Sollecito. He is now under investigation by the Florence chief prosecutor and could face millions in damages and further years in prison. So could his publishers Simon & Schuster and his shadow-writer Andrew Gumbel.

Not to mention that Sollecito is probably wrecking any chances he had at the repeat of the appeal. Does Amanda Knox REALLY want to be in the same boat? And do her shadow-writer and her publishers too?

Here are our other previous posts on her book:

- Were Prospective Knox Publishers Given The Full Score On The Likely Legal Future Of This Case?

- HarperCollins: A Commendably Balanced Report By The UK Daily Telegraph’s Iain Hollingshead

- HarperCollins: Perhaps This Explains Why Jonathan Burnham Was Inspired To Take Such A Seeming Risk

- My Letter To Claire Wachtell of HarperCollins Protesting How Distasteful Knox’s Book Promises To Be

Below: The HarperCollins US publicist Tina Andreadis (aka Tina Eleni) participated in the very very very odd Twitter exchange at bottom. She seems unfamiliar with the concept of “contempt of court” and the criminal and civil nightmares headed Simon & Schuster’s and Sollcito’s way.

Perhaps Tina Andreadis was out of the loop when her publishing company did its due diligence.

Thanks to our main poster Bedelia for this astonishing catch.

Monday, April 08, 2013

Experienced Trial Lawyer: There’s Far More Evidence Than UK/US Courts Need For Guilt

Posted by SomeAlibi

The false claim “there is no evidence”

Some amateur supporters of Knox and Sollecito have committed thousands of hours online to try and blur and obfuscate the facts of the case in front of the general public.

Their goal is simple: to create an overwhelming meme that there is “no evidence” against the accused, and thereby try to create a groundswell of support. Curt Knox and Edda Mellas and Ted Simon have all made this “no evidence” claim many times.

At least some some of the media have eagerly swallowed it.

The amateur PR flunkies make up myriad alternate versions of what created single points of evidence, often xenophobic scare stories designed to trigger emotional reactions, which they hope will be repeated often enough to become accepted as “the truth”.

And where things get really tricky, another time honored tactic is to go on at great length about irrelevant details, essentially to filibuster, in the hope that general observers will lose patience with trying to work it all out.

But time and again we have shown there is actually a great deal of evidence.

Evidence is the raw stuff of criminal cases. Let me speak here as a lawyer. Do you know how many evidence points are required to prove Guilt? One evidence point if it is definitive.

A definitive evidence point

If you’re new to this case or undecided, what is an easy example of ONE definitive evidence item that might stand alone? Might quickly, simply, and overwhelmingly convince you to invest more time into understanding the real evidence, not that distorted by the PR campaign?

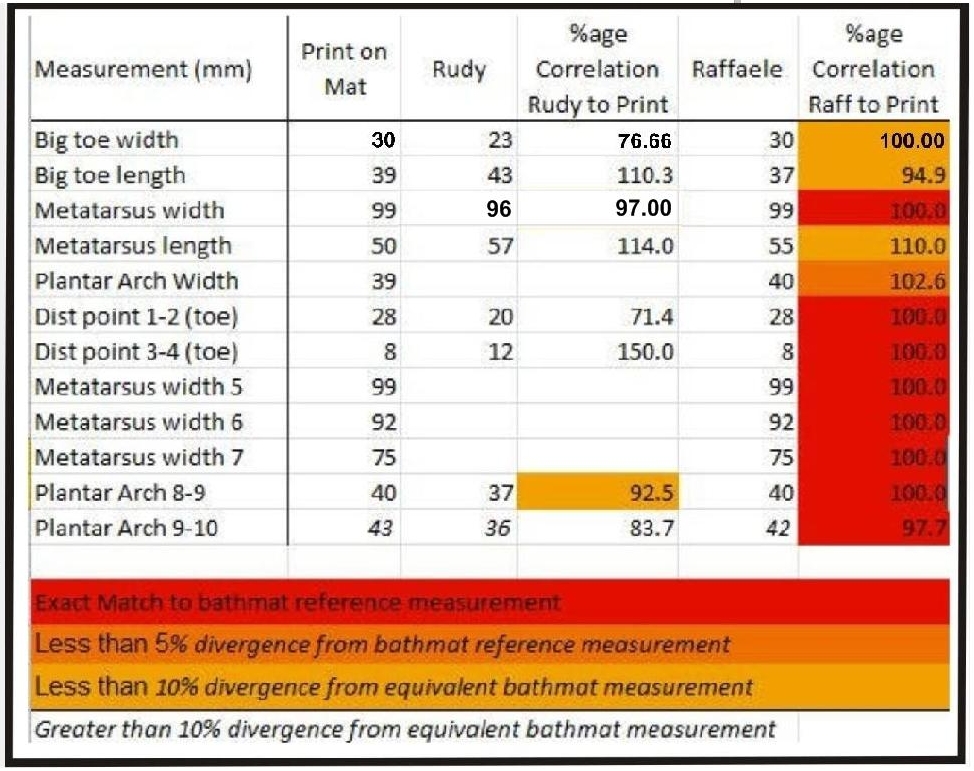

In fact we have quite a choice. See the footprint which was second on that list.

Now see the table above. I recommend the use of this table of measurement to avoid the lengthy back and forward of narrative argument which so lends itself to obscuring the truth. I would like to present you with this single table of measurements to give you pause to question whether this line that there is “no evidence” is really true or whether it might be a crafted deception.

I present here a summarized view of critical evidence which suggests with devastating clarity that Raffaele Sollecito was present the night of the murder of Meredith Kercher. No lengthy text, no alternate versions, just measurements.

This FIRMLY places Sollecito in the very room where Meredith was attacked and killed.

In the small bathroom right next to Meredith’s bedroom was a bathmat. On it was found a bloody naked right footprint of someone walking straight towards the shower in the bathroom. The blood is that of Meredith.

The footprint is not Amanda Knox’s - it is too big - but we can compare it to the prints taken of Rudy Guede and Raffaele Sollecito.

In Judge Massei’s report the multiple measurements were detailed in the narrative over many sentences and, in that form, their immediate cumulative impact is less obvious. It is only by tabulating them, that we are forcefully hit by not one but two clear impressions:

The measurements are extremely highly correlated to the right foot of Raffaele Sollecito in twelve separate individual measurements. In themselves they would be enough for a verdict of guilt in all but a few court cases.

But they also show a manifest LACK of correlation to the right foot of Rudy Guede, the only other male in that cottage on the night. Have a look for yourself.

If you were the prosecution, or indeed the jury, and you saw these measurements of Raffaele’s foot versus the print, what would you think? Answer the question for yourself based on the evidence admitted to court.

Then, if you compare further, exactly how plausible do you find it that the measurements of the bloody imprint are Rudy Guede’s instead?

Not only are some of the individual measurements of Rudy’s imprint as much as 30% too small, but the relative proportions of length and breadth measurements are entirely wrong as well, both undershooting and overshooting by a large margin (70% to 150%).

Conclusions that must follow

Presented with those numbers, would you consider those measurements of Rudy Guede’s right foot to show any credible correlation to those of the footprint on the mat?

Supporters of the two have tried frantically to create smoke screen around this - the wrong technique was used they say (ruled not so by the court) / they are the wrong measurements (all 32 of them? that Raffaele’s are matching exactly or within a millimetre but Rudy’s are out by as much as -30% to +50%...?).

The severity of the impact on the defence is such that there was even a distorted photoshopped version circulated by online supporters of Raffaele and Amanda until they were caught out early on in coverage. But it is hopeless, because these are pure measurement taken against a scale that was presented in court and the data sits before you.

Have a look at the measurements and understand this was evidence presented in court. Whose foot do you think was in that bathroom that night? Rudy Guede? Or was it Raffaele Sollecito on twelve counts of measurement?

And if you find for the latter, you must consider very seriously what that tells you both about the idea there is “no evidence” in this case and who was in the cottage that night…

Wednesday, April 03, 2013

The Real Catastrophe For The Defenses That Was The Chieffi Supreme Court Ruling

Posted by Machiavelli

1. Overview

On Tuesday March 26, nine judges of the Rome Supreme Court of Cassation led by the respected Dr Chieffi quashed the previous acquittals of Amanda Knox and Raffaele Sollecito for the murder of Meredith Kercher.

The Supreme Court annulled almost the entirety of the 2011 Hellmann-Zanetti appeal verdicts, declaring the appeal outcome completely invalid on five of the six charges. The Court only upheld the sixth charge which made definitive Knox’s conviction for calunnia for which she had been sentenced to three years.

Calunnia is the crime of maliciously placing false evidence or testimony against an innocent person, something the Italian Criminal Code considers not as criminal defamation but as a form of obstruction of justice, a more serious offence.

Worse for Knox, the Court annulled a part of the appeal verdict which had dropped the aggravation known as continuance, the aggravation that acknowledges a logical link between the obstruction of justice and the murder charge.

2. First reactions

Once the dust has settled, the defendants and pro-Knox and pro-Sollecito supporters and defences may finally realize how severe a defeat has been dealt to their side.

Most American journalists were completely unprepared for and very surprised at the outcome. But most Italian commenters and a very few others elsewhere considered the outcome quite predictable (the criminologist Roberta Bruzzone for example hinted so in written articles, so did Judge Simonetta Matone, as well as John Kercher in his book, and many others too).

This really is a catastrophe for the defences. A complete annulment of an acquittal verdict is just not frequent at all. They do occasionally occur, though, and this one appeared easily predictable because of the extremely low quality of the appeal verdict report.

For myself I could hardly imagine a survival of the Pratillo Hellmann-Zanetti outcome as being realistic.

I previously posted at length on the Galati-Costagliola recourse (that is an important read if you want to understand all angles of the annulment). I argued there that a Supreme Court acceptance of the verdict would have so jeopardized the Italian jurisprudence precedents on circumstantial evidence that it would have become impossible to convict anyone in Italy at all.

The previous appeal trial obviously violated the Judicial Code as it was based on illegitimate moves such the appointing of new DNA experts for unacceptable reasons. It contained patent violations of jurisprudence such as the unjustified dismissal of Rudy Guede’s verdict on a subset of the circumstantial evidence. Hellmann-Zanetti even “interpreted” the Constitution instead of quoting Constitutional Court jurisprudence.